Quick answer: Ringworm in cats is a contagious fungal skin infection (not a worm) that usually causes round bald patches, flaky or red skin, and mild itching. It spreads through spores to other cats, dogs, and even people, but with vet-prescribed antifungal treatment and thorough home cleaning, most cats make a full recovery.

Índice

Introduction: Ringworm In Cats

We know how scary it is to suddenly find a bald patch on your cat. Your mind jumps to ringworm, you start worrying about your other pets, and maybe even about your kids. The good news is that ringworm in cats is very treatable, and you don’t have to figure it out alone.

As the SnuggleSouls team, we’ve dealt with ringworm firsthand in our own cats and foster kitties. In this guide, we’ll walk you through:

- How to recognize ringworm in cats (what it really looks like)

- How it spreads and how contagious it is to humans and other pets

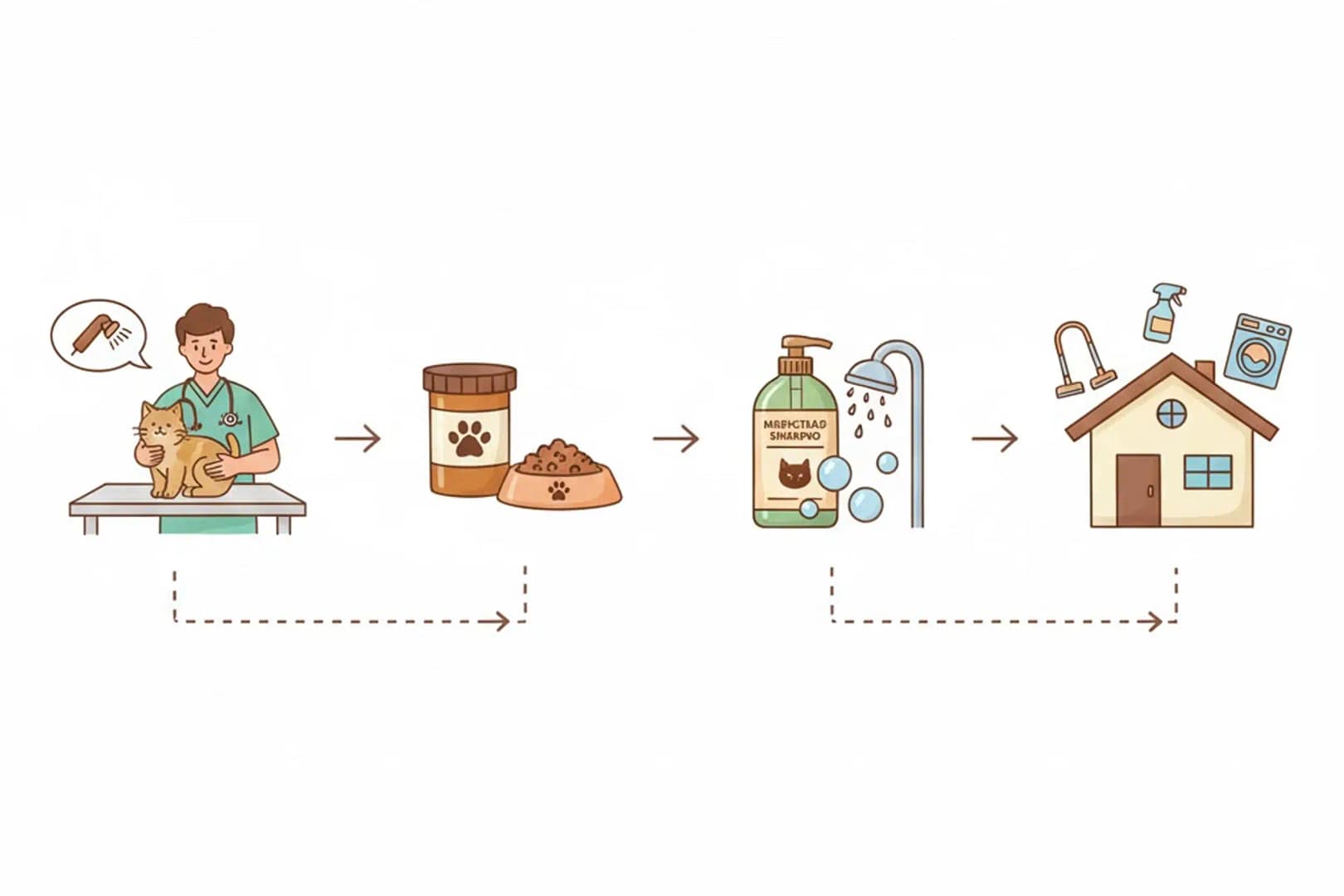

- Step-by-step treatment options your vet may recommend

- Exactly how to clean your home so the fungus doesn’t keep coming back

Our goal is to give you practical, science-based steps you can start using today: what to watch for on your cat’s skin, when to call your vet, how to set up a “sick room,” and how to protect the rest of your household. By the end, you’ll know what’s happening, what to do next, and what recovery realistically looks like.

In the next section, we’ll give you a quick snapshot of the most important points about ringworm in cats, so you can see the whole journey before we dive into the details.

Principales conclusiones

- Ringworm is a fungal skin infection, not a worm. It usually causes round bald patches, flaky or red skin, and mild itchiness. It’s contagious to other pets and people, but very treatable.

- Suspect ringworm if you see new bald, scaly spots. Lesions often appear on the head, ears, tail, or paws. If one pet is diagnosed, assume others in the home may have been exposed.

- Let your vet confirm the diagnosis. They may use a Wood’s lamp, fungal culture, PCR, or microscope exam. This avoids mistreating other skin diseases and helps choose the right treatment plan.

- Most cats need both topical and oral antifungal treatment for 4–6+ weeks. Medicated shampoos/dips plus prescription pills (like itraconazole or terbinafine) are common. Don’t stop early, even if the skin looks better.

- Isolate the infected cat and practice good hygiene. Keep them in an easy-to-clean room, wear gloves, wash hands well, and limit contact for children, elderly, and immunocompromised family members.

- Clean your home consistently to remove spores. Vacuum often, wash bedding on hot, and disinfect hard surfaces (e.g., 1:10 bleach on bleach-safe areas). This prevents re-infection and protects other pets.

- Be patient, and focus on prevention going forward. It can take weeks to fully clear ringworm. Support your cat with gentle handling, treats, and low stress, and quarantine new pets for a couple of weeks to reduce future risk.

With those big-picture points in mind, let’s look more closely at what ringworm in cats actually is and why vets take it seriously in the first place.

What Is Ringworm in Cats (and Why Is It a Concern)?

Ringworm in cats is a fungal infection of the skin, hair, and sometimes claws. Despite the name, there are no worms involved. The fungi responsible are called dermatophytes, and they feed on keratin, the protein that makes up your cat’s fur, outer skin, and nails. They live in the top layers of the skin and hair follicles and cause patches of hair loss and irritation.

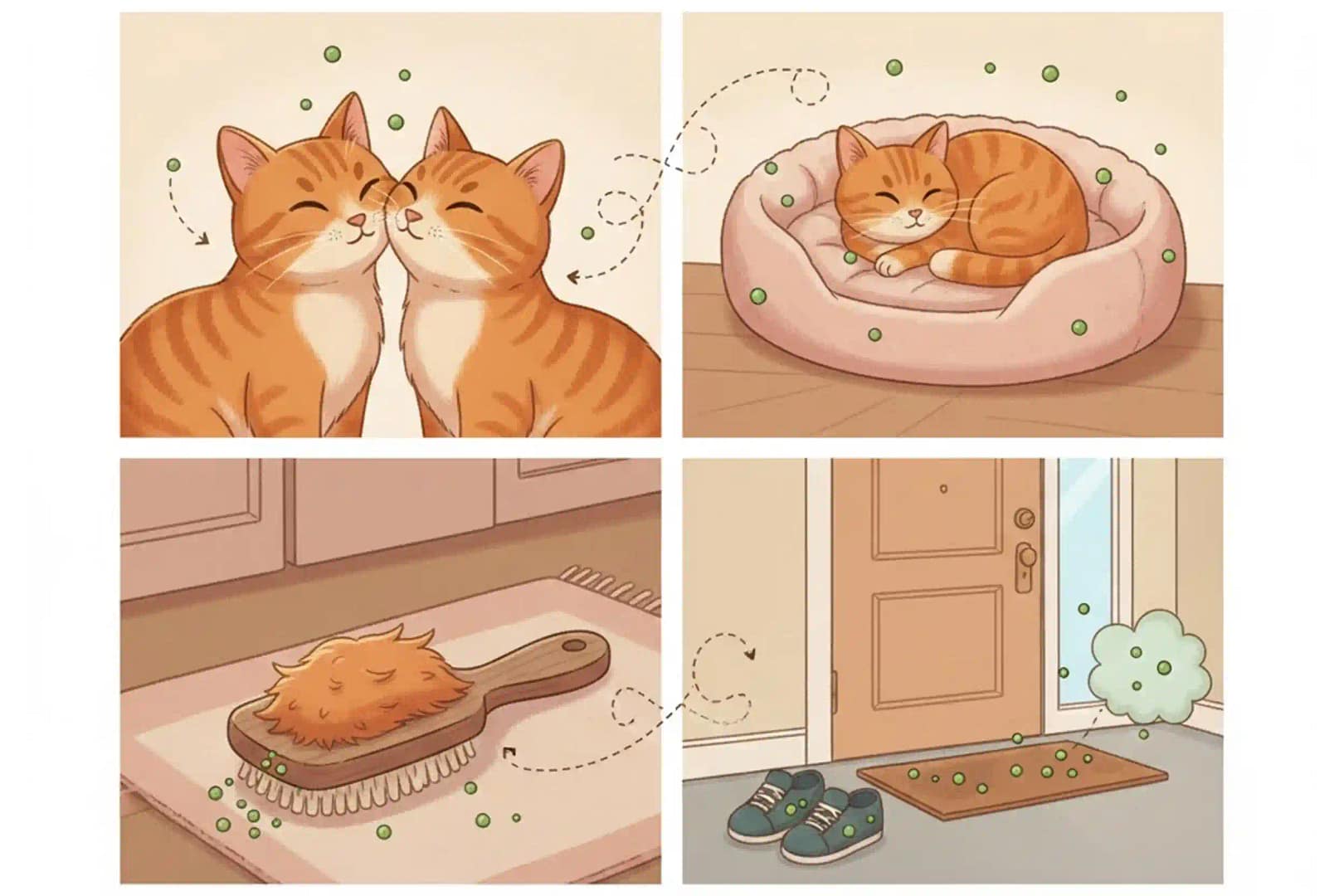

These fungi are microscopic and widespread in the environment. They thrive in warm, humid conditions and can lurk in soil, dust, carpets, bedding, and on grooming tools. During infection, they produce huge numbers of tiny spores (think of them as fungal “seeds”). Those spores stick to hair, skin flakes, furniture, and clothing and can remain infectious in your home for many months if not cleaned properly. That’s why even a strictly indoor cat can get ringworm—you might unknowingly carry spores in on your shoes, clothes, or hands.

La buena noticia es que not every exposure leads to infection. A healthy adult cat’s immune system and grooming habits often remove or kill spores before they cause trouble. Problems arise when:

- A cat is very young, very old, or has a weakened immune system

- The environment is heavily contaminated (for example, a shelter or multi-cat home)

- The cat has long, dense fur that traps spores close to the skin

Ringworm is also zoonosis, meaning it can spread between animals and people. If your cat has ringworm, you and your family can develop a red, ring-shaped rash where spores reach the skin. Children, elderly people, and anyone with a weakened immune system are more at risk—but in most healthy humans it’s mild and easily treated with standard antifungal creams.

All of this is why ringworm matters: it’s contagious, persistent in the environment, and annoying to treat if you ignore it. The upside is that with proper veterinary treatment and good cleaning routines, most cats make a full recovery and your home can be cleared of spores.

Now that we’ve covered what ringworm is and why it matters, the next step is learning exactly what it looks like on a real cat so you can spot it early at home.

Ringworm in Cats Symptoms: What Does It Look Like?

The most classic symptom of ringworm in cats is a round bald patch with flaky or scaly skin, often on the head, ears, face, paws, or tail. Some cats only have one or two small spots; others develop multiple lesions or a generally rough, scruffy coat. Below, we’ll walk through the common signs so you can compare them to what you’re seeing on your own cat.

A small bald patch on a cat’s front leg, typical of a ringworm lesion. This round, hairless spot with mild redness and scaliness is a hallmark sign of ringworm infection. Cats often develop circular patches of fur loss with a red or gray scaly center. If you notice a lesion like this on your cat, ringworm could be the culprit – although keep in mind that other skin conditions can look similar, so a vet check is important for confirmation.

En clearest sign of ringworm in cats is a patch of caída del cabello that often has a circular or oval shape. The skin in that area may appear reddish, scabby, or flaky. You might see a ring of more inflamed skin at the edges of the lesion, with a more normal-looking center – especially if it’s healing.

Common spots for these lesions are the head, ears, face, paws, and tail, but they can occur anywhere. For example, one of our foster kittens at SnuggleSouls had a ringworm patch right on the ear tip, while another cat developed a bald spot on her tail. It can vary from cat to cat, so it’s good to do a nose-to-tail check if you suspect something.

Early signs of ringworm in cats you can spot at home

Aside from the classic bald circles, here are other symptoms and changes you might observe:

- Scaly or crusty skin: The bald areas often have dry, gray or tan scaling on them – almost like dandruff or eczema in appearance. In some cases, there might be a thin crust. This happens as the fungus irritates the skin.

- Broken or brittle fur: You might notice the hair around the lesion is broken off and stubbly, or that your cat’s coat looks dull and rough overall. Ringworm weakens the hair shafts, causing them to break.

- Redness and bumps: The skin can be a bit red and inflamed. Some cats develop small raised bumps or pustules (a condition called miliary dermatitis) in response to the fungus. In severe cases, lesions can become larger lumps with sores (called kerions), though this is less common.

- Itching or grooming: Ringworm isn’t as insanely itchy as, say, flea allergies, but many cats will groom or scratch the affected areas more than usual. If you see your cat obsessively cleaning one spot or notice increased scratching, take a closer look at the skin there.

- Nail/claw issues: Rarely, ringworm can infect the claws, causing them to appear rough, cracked or deformed. You might see a crust around the nail bed. This is uncommon, but if your cat’s nails look abnormal, mention it to your vet.

- General coat quality: Some cats just start looking a bit “off” – slightly scruffy fur or more dandruff. A formerly glossy coat might turn dry or patchy. These subtle changes can be a hint, especially in long-haired cats where individual lesions might be hidden under fur.

It’s critical to know that some cats show no visible symptoms at all. These are so-called asymptomatic carriers. In our experience, this tends to happen with otherwise healthy adult cats who carry the fungus on their fur but don’t develop lesions.

Unfortunately, they can still spread ringworm to other pets or people. For example, you might have one cat with obvious ringworm patches and another cat in the same home who looks perfectly fine but ends up testing positive too.

This is why, if one pet in your home has ringworm, we assume all pets have been exposed and should be checked or treated as well.

Real-life playbook: The tiny bald spot we almost ignored

Setup: We were fostering a litter of otherwise healthy kittens. Everyone looked great—bright eyes, good appetite, glossy coats. During a routine cuddle-and-groom session, we noticed a pea-sized bald spot on one tabby’s ear. It wasn’t very red or itchy, and she was playing normally.

Problem: It would have been easy to shrug it off as rough play or a scratch. But over a few days, the spot didn’t grow fur back. Instead, the center looked a bit flaky and gray, and the edges were slightly more defined. We started worrying this wasn’t just a random scab.

Steps we took:

- We took clear photos of the spot and watched it for 2–3 days instead of guessing.

- When it slowly widened and stayed scaly, we booked a vet visit and mentioned ringworm as a concern.

- The vet did a Wood’s lamp check and collected hairs for a fungal culture, then started topical and oral antifungal treatment while we waited for results.

- We treated her as if she had ringworm from day one: set up a “sick room”, changed clothes after handling her, and flagged the litter as exposed.

Outcome: The culture came back positive for ringworm, but because we caught it early, only that kitten had visible lesions. The others were monitored closely and had much milder cases. The outbreak stayed contained to one room, and all of them cleared with a single treatment course.

How this helps you: If you see a new bald spot—especially one that’s flaky or slowly growing—treat it as “ringworm until proven otherwise”. Compare what you see with the signs in this symptoms section, take photos, and call your vet early instead of waiting weeks to see what happens.

If these signs are starting to look familiar, the next natural question is how your cat picked up ringworm in the first place—and which risk factors might be at play.

How Do Cats Get Ringworm? Causes, Risk Factors & Incubation

Most cats catch ringworm by coming into contact with infected animals or contaminated environments – things like shared bedding, grooming tools, carpets, or soil where an infected cat has shed fur. The spores are microscopic and very hardy, so even indoor cats can be exposed. Age, stress, long fur, and underlying illness all increase the risk, and signs typically show up 1–3 weeks after exposure.

Main ways cats get ringworm

- Direct contact with an infected animal: Wrestling, grooming, or even brief contact with an infected cat, dog, or small pet can transfer spores onto your cat’s fur and skin.

- Contaminated environment: Infected hairs and skin flakes fall into the environment and shed spores everywhere. Beds, carpets, cat trees, carriers, grooming tables, garden soil—any place an infected animal spends time can become a “spore hotspot.” Spores are sticky and can stay infectious for many months, even after the original cat is gone.

- Grooming tools and human hands: Brushes, combs, towels, and even your hands or clothes can ferry spores from one animal to another. That’s why sharing grooming tools or handling lots of cats in a shelter or foster setting makes hygiene so important.

Which cats are at higher risk?

- Kittens under one year (immature immune system)

- Gatos mayores and cats with illnesses like FIV/FeLV or diabetes

- Long-haired breeds, where dense fur traps moisture and spores close to the skin

- Cats in crowded, stressful conditions, such as shelters, catteries, pet shops, or busy multi-cat homes

- Cats in warm, humid climates, where fungi thrive

After exposure, the incubation period is usually 1–3 weeks. That means your cat might meet an infected animal or walk through a contaminated area and only show hair loss and skin changes a couple of weeks later.

One case we often see: a kitten adopted from a shelter looks perfectly healthy at first, then develops a tiny bald spot after a week or two at home. Often there was a littermate with ringworm, and the “healthy” kitten was just an asymptomatic carrier until the stress of moving let the fungus get ahead. This is why we encourage a short quarantine and careful skin checks for any new cat coming into your home.

Understanding how ringworm spreads and which cats are most at risk leads straight to the next big concern: who else in your home—pets or people—might catch it.

Is Ringworm in Cats Contagious to Humans and Other Pets?

Yes. Ringworm in cats is zoonosis, which means it can spread between animals and people. The same fungal spores that live on your cat’s fur and skin can infect other cats, dogs, and humans if they make contact with broken skin or hair.

In people, ringworm usually shows up as a small, red, itchy circular rash—often on the arms, hands, or body where you’ve touched the cat or bedding. It can look a bit like a mosquito bite at first, then slowly expand with a clearer center. Luckily, in healthy adults, it’s usually mild and easily treated with over-the-counter antifungal creams (always follow your doctor’s advice).

Who needs extra caution?

- Young children who love to cuddle and may not wash their hands well

- Older adults

- People with weakened immune systems (because of medications, chronic illness, chemotherapy, etc.)

- Anyone with eczema or frequent skin breaks, which give spores an easier way in

If anyone in your home falls into these groups, it’s wise to:

- Keep them from handling the infected cat until your vet says the risk is low

- Make sure they wash hands after touching any shared surfaces or laundry

- Avoid letting them nap on the infected cat’s bed or near the isolation room

- Ask their human doctor for advice if they notice any skin rash at all

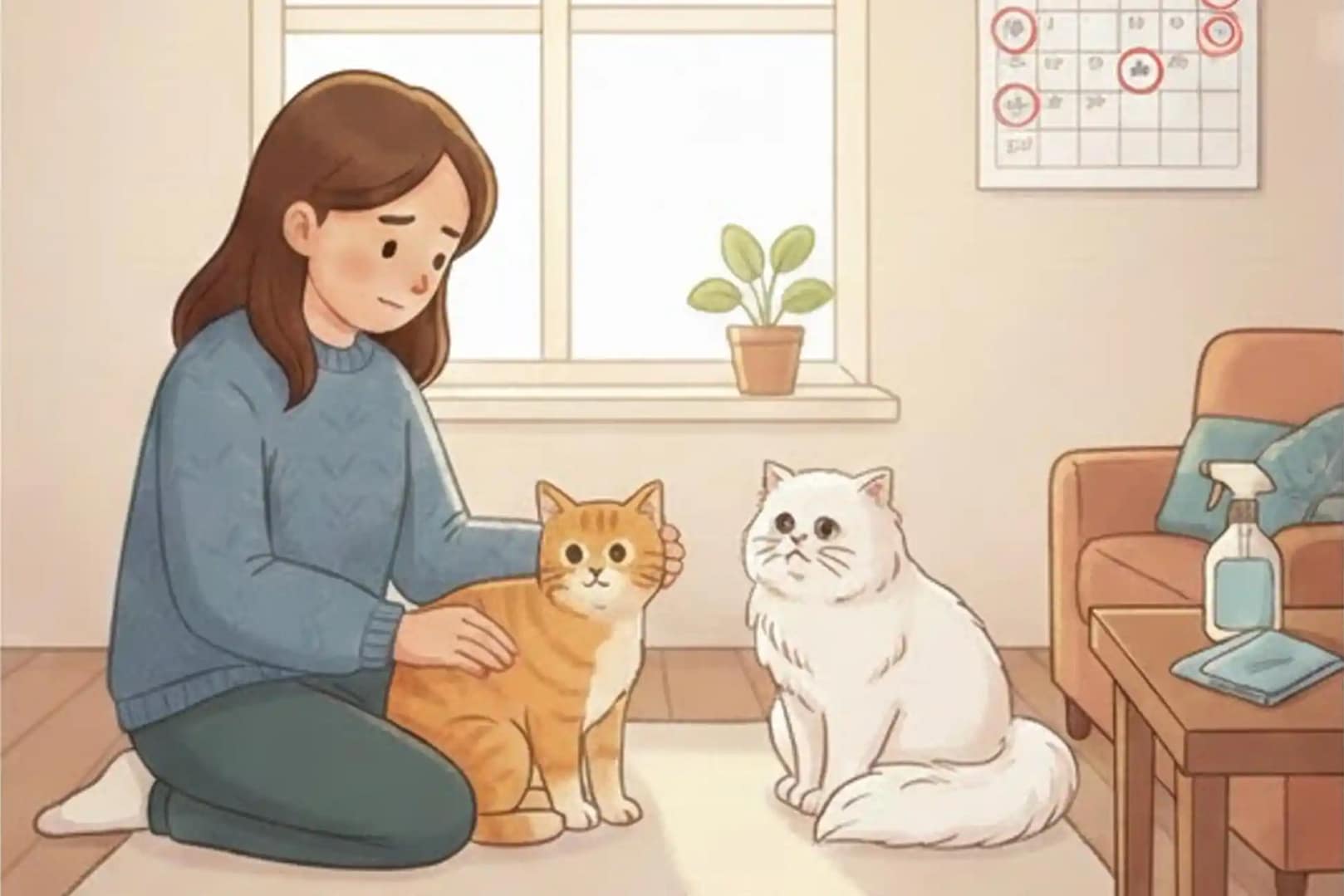

Other pets can also catch ringworm, especially kittens, puppies, and long-haired animals. If one cat is diagnosed, we assume every animal in the home has been exposed. Speak with your vet about whether to test or proactively treat your other pets, and monitor everyone for new bald patches or scaly spots over the next few weeks.

Next, we’ll talk about diagnosing ringworm properly, which often means a trip to the vet for some simple tests. This step is crucial to differentiate ringworm from other skin issues and to form a solid treatment plan.

Because ringworm can spread quietly and mimic other skin problems, the safest next step is to see how your vet can confirm what’s really going on with a proper diagnosis.

How Do Vets Diagnose Ringworm in Cats?

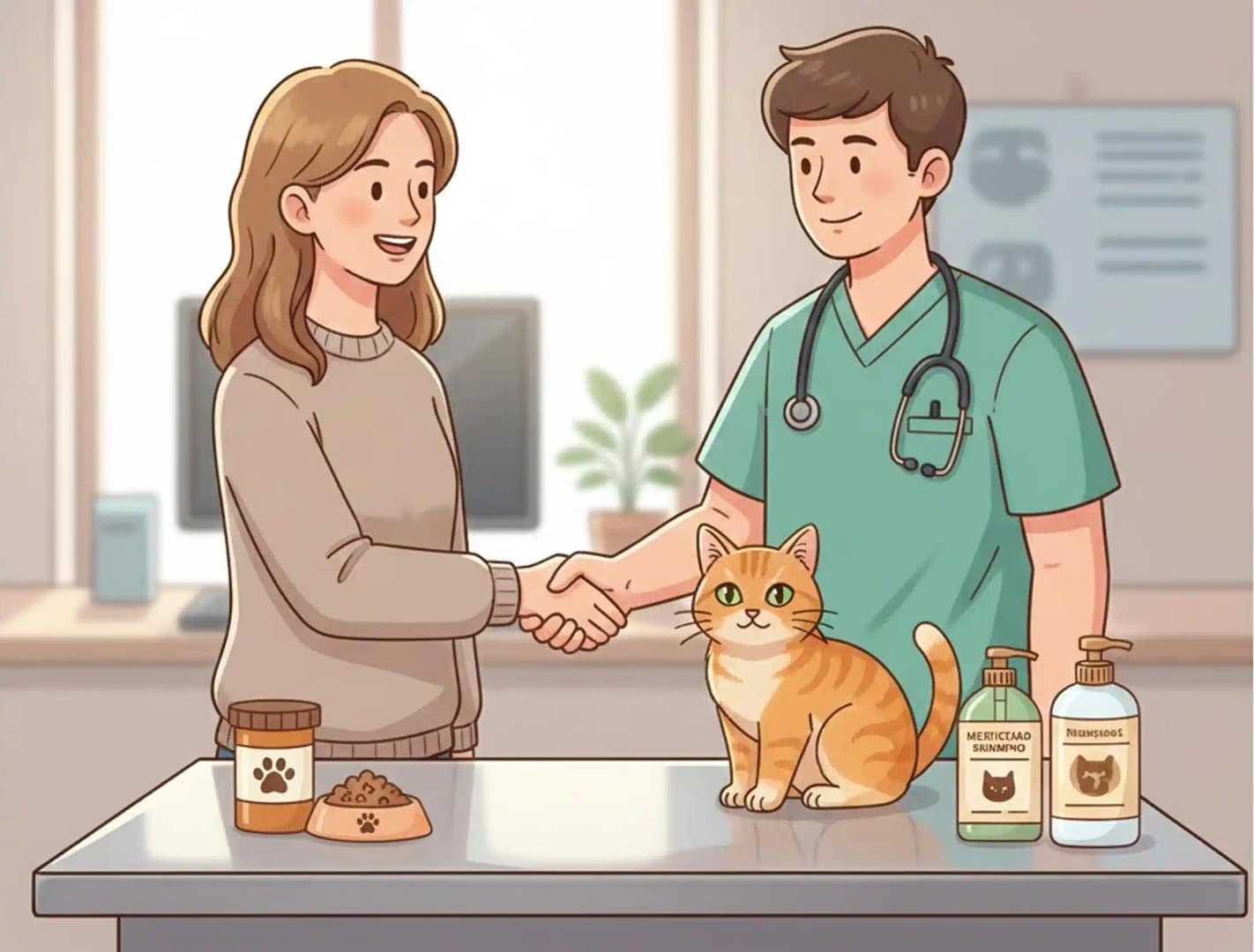

Because ringworm can look like other skin problems, your vet will usually confirm it with one or more simple tests rather than guessing. Most clinics combine a careful skin exam with a Wood’s lamp check, and then send samples for a fungal culture or PCR test if they want a definite answer and to know when the infection is truly gone.

If you suspect ringworm, we highly recommend bringing your cat to the vet for a proper diagnosis. In our experience, this is a key step.

Because other conditions (like allergies, mites, or bacterial infections) can resemble ringworm, you want to be sure of what you’re dealing with. Plus, treating ringworm often involves prescription medications and a strategic plan – something your veterinarian can guide you through.

At the vet’s office, here’s what you can typically expect for a ringworm evaluation:

- Physical examination: The vet will closely inspect your cat’s lesions and overall coat. Vets who have seen lots of ringworm often develop a good “eye” for it. They might note the pattern of hair loss, any glow under a lamp (more on that below), or whether the claws are involved.

- Wood’s lamp test: Many vets use a Wood’s lamp, which is a special ultraviolet light that can cause certain ringworm fungi (particularly Microsporum canis) to glow apple-green under the light. They’ll take your cat in a dark room and shine this lamp over the fur. If a lesion or hair shaft fluoresces green, it strongly suggests ringworm. However, not all ringworm strains glow – so a negative Wood’s lamp test doesn’t completely rule it out. Also, other substances (like ointments or skin debris) can sometimes fluoresce, so vets usually confirm with additional tests.

- Fungal culture: This is considered the patrón oro for diagnosis. The vet will pluck some hairs and skin scales from the affected area and place them on a special culture medium to see if the ringworm fungus grows. This test is very accurate, but it takes time – often De 1 a 3 semanas for a definitive result because the fungus needs to grow in the lab. Waiting for culture results can be frustrating, but it’s the best way to know when your cat is truly clear of infection later on.

- Microscopic exam: The vet may also examine hairs or skin scrapings under a microscope to look for fungal spores or filaments. It’s a quick test done in-house. If they see the spores attached to hair, that’s a immediate confirmation. However, it requires skill and even then can miss a case, so it’s often done in conjunction with a culture.

- PCR testing: Some veterinary labs offer PCR (polymerase chain reaction) tests that detect ringworm DNA in samples. The advantage is speed (results in a few days), but PCR can sometimes pick up dead spores or non-infective bits, so it’s usually used alongside other methods rather than alone.

- Other diagnostics: In rare stubborn cases, a vet might do a skin biopsy or other advanced tests, but this is seldom needed unless they suspect something else is complicating the picture.

From a pet owner’s perspective, what you’ll actually see is your vet possibly shining the UV light, tugging out some fur (your cat might not love that moment, but it’s quick), maybe brushing the cat with a sterile toothbrush (another method to collect samples), and then starting treatment if ringworm is suspected even before culture results return (based on exam and initial tests).

Don’t be surprised if your vet sends you home with medication on the first visit, especially if the signs strongly point to ringworm – it’s better to start addressing it than wait weeks. They might call you later with culture confirmation or a clear result and adjust the plan if needed.

A veterinarian handling a cat with protective gloves during an exam. When examining a cat for ringworm, vets often use gloves and disinfect between patients to avoid spreading the fungus. We always appreciate this level of caution.

Once a diagnosis is confirmed (or strongly suspected), your vet will discuss a treatment plan with you. This usually involves antifungal medications for your cat and advice on cleaning your home environment. Open communication with your vet is key – don’t hesitate to ask questions about how to give the meds or how to manage things at home.

Our SnuggleSouls team makes it a point to clarify all steps with the vet whenever we handle a ringworm case, because a clear plan reduces stress for both you and your cat.

Finally, remember to inform your vet if other pets or family members have any symptoms (like if you developed a skin rash). They can give you guidance on protecting everyone.

Also, let the vet know if your cat has any other health issues or is on medications, as this could influence the treatment choice. Getting a definitive diagnosis of ringworm can be a relief in a way – you know what the problem is and that it’s treatable.

Once you know how ringworm is diagnosed, the obvious next question is what treatment actually looks like day to day—and how to turn your vet’s plan into simple, repeatable steps at home.

How Do You Treat Ringworm in Cats? Step-by-Step

Treating ringworm in cats means tackling three things at once:

- Killing the fungus on your cat

- Stopping it from spreading to other pets and people

- Cleaning up the spores in your home

Most cats need a mix of vet-prescribed oral medication, medicated baths or dipsy un repeatable home-cleaning routine for several weeks. Here’s how to break it down into manageable steps.

Step 1: See your vet and start antifungal treatment

Your veterinarian will examine your cat and, if ringworm is likely, start treatment while tests are pending. Most cats are treated with a combination of:

- Topical therapy – medicated shampoos or dips (for example, miconazole + chlorhexidine or lime sulfur) to kill fungus on the skin and fur

- Oral antifungal medication – such as itraconazole or terbinafine, to attack the infection from the inside out

Topical treatments are usually used once or twice a week. Oral meds often continue for 4–6 weeks or longer, depending on how severe the infection is and whether tests show that the fungus is gone. It’s essential to finish the full course, even when your cat looks much better. Stopping early is one of the most common reasons ringworm comes back.

If your cat is hard to medicate, let your vet know. They may suggest flavored liquids, pill pockets, compounding, or occasionally different drug choices. Also watch for side effects such as vomiting, poor appetite, or unusual tiredness, and report anything worrying to your vet—they may adjust the dose or run a blood test to check liver values.

Step 2: Isolate your cat to contain spores

While the meds are working, set up a simple “sick room”:

- Choose an easy-to-clean room (bathroom, spare room with hard flooring).

- Give your cat their own litter box, food and water bowls, bedding, and toys that you can wash or disinfect.

- Keep children, elderly, and immunocompromised family members out of this room.

- When you go in, wear gloves and a “ringworm outfit” (shirt/apron you can wash in hot water), and wash your hands thoroughly when you leave.

Isolation is temporary but very effective: it keeps most spores in one zone so you can clean more easily and protects your other pets.

Step 3: Clean the environment consistently

Managing ringworm is roughly 50% treating the cat and 50% decontaminating the environment. Focus on a routine you can actually stick to:

- Diario

- Vacuum or sweep the sick room to remove hair and skin flakes.

- Wipe hard surfaces (litter box area, floors, shelves) with a 1:10 diluted bleach solution or vet-approved fungicidal cleaner (on bleach-safe surfaces). Let it sit ~10 minutes before wiping off.

- Several times per week

- Wash the cat’s bedding, your “ringworm clothes”, and any washable blankets in hot water and detergent, plus bleach if the fabric tolerates it.

- Vacuum shared areas where the cat spent time antes de isolation—sofas, carpets, window perches.

- Semanal

- Mop hard floors throughout your home.

- Consider steam cleaning carpets and upholstery if you can (heat helps kill spores).

Always dispose of vacuum contents right away, ideally sealed in a bag. Damp dust instead of dry dusting so you don’t fling spores into the air.

Step 4: Treat or monitor other pets and follow up with your vet

If you live with multiple cats or other animals, assume everyone has been exposed. Discuss with your vet whether to:

- Monitor closely and only treat pets that develop lesions, or

- Test exposed animals (cultures or PCR) to see who is infected, or

- Treat all cats in the household, especially in long-haired or high-risk animals

Your vet will usually recheck your cat after a few weeks of treatment. Many follow a protocol of continuing meds until your cat is clinically normal and has one or two negative fungal cultures or PCR tests about two weeks apart. That way, you’re not stopping treatment while the fungus is still quietly hanging on.

At-home care for a cat with ringworm

While the meds are fighting the fungus on your cat, your job at home is to stop the spread of ringworm spores and clean up the ones that are already shed. This is arguably the toughest part, but it’s extremely important.

Without environmental cleaning, your cat could get re-infected from the lingering spores even after treatment. We often say managing ringworm is 50% treating the cat and 50% decontaminating the environment.

Here’s a practical plan for home care and cleaning:

Isolating the infected cat

If possible, confine your ringworm-positive cat to a “sick room” or one area of the house during treatment. A easy-to-clean room (like a bathroom or a room with hard floors and minimal upholstery) is ideal.

This limits the spread of spores to the rest of your home. Set up a comfy quarantine space with the cat’s food, water, litter box, and some toys that can be easily cleaned.

We know it’s hard to separate your cat, but it’s temporary and helps everyone. Spend time with them in that room to keep them company (wearing protective clothing as noted below), so they don’t feel too isolated.

If you have an empty spare bedroom, that can work – perhaps remove any throw rugs or fabrics that are hard to wash. Ventilate the room if you’re using disinfectants, but avoid spreading spores through airflow to other areas (keeping the door closed is usually fine).

Handling and hygiene (gloves, handwashing, kids)

Whenever you handle your infected cat or clean their room, wear disposable gloves and even a simple apron or dedicated long-sleeve shirt that you remove afterwards. This keeps spores off your skin and clothes. After each session, wash your hands thoroughly with soap and hot water. It might help to have a “work outfit” for ringworm chores that you then launder in hot water.

If you have kids, it’s best that they don’t handle the infected cat until you’ve got the all-clear, especially young children. The same goes for any immunocompromised family members.

We turn ringworm care into a bit of a routine: for example, each morning and evening one of us on the team (wearing gloves) will feed and medicate the isolated cat, give them cuddles (with gloves on), then dispose of gloves and wash up.

This containment and hygiene routine greatly reduces the risk of humans getting ringworm or tracking spores around.

Cleaning surfaces and items

Fungus spores can be killed by disinfectants like bleach and some veterinary disinfectant solutions. A tried-and-true solution is 1:10 diluted bleach (one part bleach to ten parts water) applied to surfaces that can tolerate it. Use this on hard surfaces such as tile floors, plastic carriers, litter boxes, etc.

Let it sit for ~10 minutes before rinsing or wiping off, as that contact time is needed to kill the spores. Be cautious: bleach can damage certain materials (don’t use it on carpet or colored fabric).

For bleach-sensitive surfaces or softer furnishings, you can use a disinfectant labeled to kill ringworm (some examples are accelerated hydrogen peroxide solutions or antifungal cleaners recommended by vets).

Clean your cat’s isolation room daily if possible: sweep or vacuum up loose hair (dispose of the vacuum bag or clean the canister with bleach afterwards), and wipe down surfaces.

Laundry

Wash the cat’s bedding, your clothes from handling them, and any washable fabric items the cat contacts. Use hot water and detergent, and add bleach if the fabric tolerates it. Dry them on high heat if possible.

Do this several times a week. It might be easiest to have a few spare cheap blankets or towels that you rotate – one set in use while another is in the wash.

In severe cases, some owners choose to throw away bedding or rugs that are heavily contaminated and hard to disinfect (for instance, that old cat tree or cardboard scratcher full of hair might be best discarded and replaced later).

Vacuuming and dusting

Vacuum all floors and furniture regularly (every 1-2 days) to pick up hair and skin flakes that carry spores. Vacuuming is your friend – it physically removes a lot of contamination.

After vacuuming, dispose of the vacuum contents carefully (treat it as biohazard: into a trash bag and out of the house). Damp dust surfaces (using a cloth with disinfectant or water) instead of dry dusting, which could send spores airborne.

Target high-risk areas

Focus on areas where your cat spent a lot of time before isolation, as those are likely “hot zones” for spores. Favorite napping spots, the cat’s litter area, sofa cushions, window perches – give them a thorough cleaning.

For upholstered furniture, vacuum and then consider using a steam cleaner if you have one, as the heat can help kill spores. We once rented a steam cleaner to go over all carpeted rooms and couches after a ringworm outbreak – it’s extra work, but it helped us feel we really reset the environment.

Continue cleaning for the duration of treatment

Don’t let up on the cleaning regimen until the vet confirms the cat is clear of ringworm. It’s tedious, we know, but this diligence pays off by truly eradicating the fungus. If you slack too early, your cat could catch it again from a missed spot.

By combining medical treatment for your cat with environmental decontamination, you’re attacking ringworm on all fronts. We often tell readers and clients: curing ringworm is a marathon, not a sprint. It might take 6-8 weeks of effort. However, most cats respond very well to treatment and start regrowing hair and acting like their normal selves within a few weeks. The infection will clear with time; the biggest challenge is managing that time effectively and keeping morale up (for both you and your kitty!).

When you’re treating ringworm one cat at a time, the plan is challenging but manageable—but if you have several cats or a foster/shelter setup, the next section will show you how to scale this routine for a whole group.

Managing Ringworm in Multi-Cat Homes and Shelters

In a one-cat household, ringworm is a headache. In a multi-cat home, foster room, or shelter, it can feel like a mini outbreak. The spores travel on fur, dust, clothes, and grooming tools, so it’s safest to assume every cat in the environment has been exposed once one positive case appears.

Step 1: Stabilize and separate

- Choose one easy-to-clean room as your “ringworm room”.

- Move the known positive cat(s) into that room with their own food, water, litter boxes, and washable bedding.

- If you have a very young, sick, or immunocompromised cat, try to keep them furthest away from the ringworm room.

- Limit who enters the room—ideally one main caregiver who can follow strict hygiene routines.

Step 2: Decide how to handle “exposed but not yet sick” cats

Talk to your vet about the best strategy for your situation. Common options include:

- Monitoring only: daily skin checks and fast action if any lesions appear (good if space or budget is limited).

- Testing (fungal cultures or PCR) on exposed cats so you know who is truly infected.

- Preventive treatment for all cats in a group, especially in shelters or catteries where separating everyone isn’t practical.

Step 3: Zoning and hygiene for the humans

- Have a “dirty zone” (ringworm room) and “clean zone” (rest of the home/shelter).

- Keep a set of clothes and shoes just for the ringworm zone if possible.

- Wear disposable gloves when handling infected cats or their litter, and wash hands and forearms thoroughly when you leave the room.

- Clean grooming tools, carriers, and litter scoops with a diluted bleach solution or a vet-recommended fungicidal disinfectant between cats.

Step 4: Cleaning strategy that you can actually sustain

In a busy cat household, the cleaning plan has to be realistic. We usually recommend:

- Daily:

- Scoop litter, pick up visible fur clumps, wipe obvious dirty spots.

- Quick vacuum or sweep of the ringworm room.

- 2–3 times per week:

- Thorough vacuum of all shared spaces the infected cats were in before isolation.

- Wash bedding, blankets, and soft toys in hot water with detergent (plus bleach if the fabric allows).

- Weekly:

- Mop hard floors with a disinfectant that kills fungal spores.

- Steam-clean or deep vacuum carpets and upholstered furniture if you have the tools.

Step 5: Reintegration

When your vet confirms that the infected cats are no longer contagious (ideally with negative cultures or PCR tests), you can slowly let them rejoin the group. Start with short, supervised sessions, and keep doing weekly skin checks on everyone for another month or so.

Having a clear multi-cat protocol turns a scary “outbreak” into a manageable routine. It’s a lot of work, but with a plan, you can protect your cats and keep your household or foster room running.

Once every cat in your household or shelter has a clear protocol, the next thing you’ll want to understand is what recovery really looks like and how long this whole ringworm chapter is likely to last.

Recovery: What to Expect and When Is It Over?

How long does ringworm in cats last?

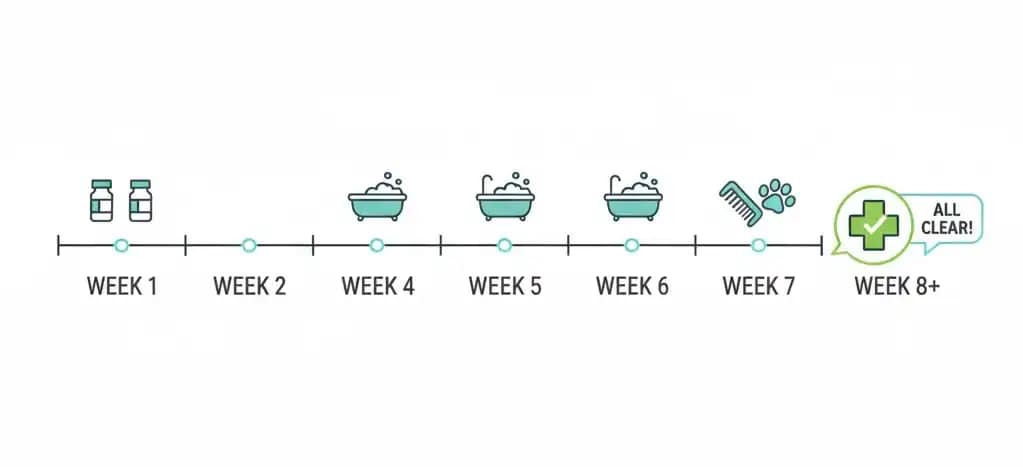

With proper treatment, most cats need at least 4–6 weeks of continuous antifungal therapy. Many will look better after 2–3 weeks, but the fungus can still be ocultar in hair follicles, so vets usually keep going until your cat is clinically better y lab tests or follow-up exams say the fungus is gone. In some stubborn cases, especially in multi-cat homes or long-haired breeds, treatment can stretch to 8-12 semanas or more.

Without treatment, ringworm in an otherwise healthy cat may eventually burn out on its own—but this can take 9–12 months, during which time your cat continues to shed spores into your home and remains contagious to other pets and people. That’s why vets strongly recommend treating ringworm rather than “waiting it out”.

To make the timeline feel more concrete, you can think of recovery in phases:

- Weeks 1–2: Start oral meds and topical baths/dips. Lesions may look the same or slightly worse at first as old hairs fall out.

- Weeks 3–4: Most cats show clear improvement—less redness, fewer new spots, and a soft fuzz of new hair appearing.

- Weeks 5–6+: Your vet may repeat a fungal culture or PCR test. Treatment often continues until there are two negative tests taken roughly two weeks apart, or until your vet is happy that the infection is fully cleared.

Emotionally, it helps to treat ringworm like a slow but winnable project. If you keep up with meds, cleaning, and vet rechecks, you’re on track—even if it feels like a long time in the moment.

When the treatment is finished and your cat is considered ringworm-free, it’s a huge relief! You can gradually relax the strict isolation and cleaning protocols.

We suggest doing a big final cleaning of the home at that point – one more vacuum of all rooms, wash all bedding, maybe replace any items you had set aside – to eliminate any straggling spores. Since you likely kept the cat confined, this final clean ensures any remaining spores outside that area are dealt with now that your cat isn’t continuously shedding more.

One silver lining: cats (and people) can develop a bit of immunity after fighting off ringworm. It’s not a guarantee they won’t get it again, but for a short time they may be more resistant. Regardless, maintain good hygiene and keep an eye out for any new patches in case of reinfection.

Behavior and mood: Don’t be surprised if your cat is a little frustrated or bored during isolation and treatment. They might be getting less play and exercise, and those twice-weekly baths sure don’t improve their mood! We try to compensate by giving our isolated cat extra affection (while suited up in gloves and all). Engage them with toys that are easy to disinfect (like a wand toy with a washable string, or plastic toys you can bleach).

Puzzle feeders or treat toys can also alleviate boredom in a confined space. After medication doses or baths, reward your cat with their favorite treats and praise. This makes the unpleasant parts a bit more tolerable.

Our team has found that a warm towel and a tasty treat right after a lime sulfur dip went a long way in keeping our kitty friend somewhat content.

Real-life playbook: The long-haired Persian who took 9 weeks to clear

Setup: We helped an owner with a long-haired Persian who suddenly developed several ringworm patches on her face and tail. Because of her thick coat and a busy multi-cat home, by the time they noticed, there were already multiple lesions and a lot of hair shedding into the environment.

Problem: En three weeks of oral itraconazole, medicated baths, and daily cleaning, the cat’s skin looked much better—less red, fewer active lesions, and new hair starting to grow. But the vet’s fungal culture was still positive, and the owner was exhausted and frustrated. It felt like they were doing everything “right” with no clear end in sight.

Steps we took:

- Reassessed the routine with their vet and confirmed they were giving meds correctly (with food, at the right time, no missed doses).

- Kept up twice-weekly baths but switched to a slightly more cat-tolerable shampoo to reduce stress.

- Tightened the cleaning routine in the cat’s favorite spots (sofa corner, windowsill, top of the cat tree).

- Accepted that, with a long-haired breed in a multi-cat home, the realistic timeline might be 8–10 weeks, not 4–6.

Outcome: Por week 7, the lesions were gone and the coat looked almost normal, but the vet advised continuing meds until cultures said “all clear.” At week 9, the first culture came back negative; two weeks later, a second culture was negative again. They finally stopped treatment, and the Persian’s coat grew back thick and beautiful. There were no new lesions on any of the other cats.

How this helps you: If your cat is long-haired, lives with multiple pets, or had a lot of lesions, it’s normal for ringworm to take longer than you hoped. If your vet is happy with your cat’s progress and your home routine, staying the course for a few extra weeks can be exactly what prevents a relapse.

When can my cat be around others again? – This is a common question. We recommend waiting until your vet confirms the cat is no longer contagious (usually via cultures or at least a vet exam and greatly improved lesions). Typically, after a few weeks of treatment the risk of contagion drops, but you don’t want to rush reintroductions and then have ringworm spread to your other pets. Follow your vet’s timeline. Once you do allow interaction, maybe start with short supervised sessions and see that no new lesions appear on any pet.

Grooming and fur regrowth: If your cat was shaved or had fur clipped, it will grow back over a couple of months. You can gently brush them (with a clean brush) to help remove any remaining flaky skin and stimulate hair growth once the infection is clearing. It’s a joy to see the coat come back shiny and full. We recall the moment when our foster kitten, who had been covered in patchy spots, finally had a solid coat of fur again – it’s very rewarding.

Most cats make a full recovery and don’t have any lasting effects from ringworm. The hair grows back, and the skin returns to normal. There’s usually no scarring unless the case was extremely severe with deep lesions (rare in cats). If a cat had a secondary bacterial infection from scratching, the vet might have treated that with antibiotics; those spots heal too.

One thing to watch for in the future: if your cat ever experiences a lot of stress or illness, keep an eye on their skin. Sometimes ringworm can recur if the cat becomes very immunocompromised. But in a healthy, happy cat, a past ringworm infection is unlikely to spontaneously return – once it’s gone, it’s gone (unless re-exposed).

Throughout recovery, continue to be kind and patient with your cat (and yourself). Ringworm is a bit of an ordeal, but it’s temporary. Many pet owners have gone through it and come out the other side with no regrets except maybe a pile of extra laundry! As you near the end of treatment, give yourself a pat on the back for sticking with it.

And when you can finally see the light at the end of the tunnel, it’s the perfect time to focus on simple prevention habits that make ringworm much less likely to come back.

How Can You Prevent Ringworm in Cats in the Future?

Once you’ve gone through a ringworm outbreak, you’ll probably do anything to avoid a repeat. While you can’t remove ringworm from the world, you puede make your cat and home much harder targets by focusing on healthy skin, low stress, sensible hygiene, and smarter introductions for new pets.

After dealing with ringworm once, you’ll probably join us in saying “Hope we never see that again!” While you can’t eliminate ringworm from the world, there are sensible steps to reduce the chances of re-infection or a new case in the future:

Maintain a clean environment

Now that you’ve done a deep cleanse of your home, try to keep up with regular cleaning. Frequent vacuuming (say, weekly) will help pick up any hair or spores that might find their way in. Wash pet bedding periodically. This general cleanliness also helps with other health issues (like reducing dust or parasites).

Healthy skin and coat

A cat with a strong immune system and healthy skin is more resistant to ringworm. Ensure your cat has good nutrition – a balanced diet rich in protein, fatty acids, and vitamins supports skin health. We always emphasize feeding high-quality food and providing fresh water.

Regular grooming can also keep the coat in good shape (and helps you spot any skin problems early). You might consider occasional baths or at least wiping down a long-haired cat if they get dirty, as spores need grime or micro-damage to take hold.

Reducir el estrés

Chronic stress can suppress the immune system. Provide a low-stress environment for your cat: give them hiding spots, playtime, and a consistent routine. In multi-cat homes, make sure there are enough resources (litter boxes, bowls, perches) to prevent tension. A less stressed cat is less likely to succumb to infections, including ringworm.

Be cautious with new pets

If you introduce a new cat or kitten to your household, it’s wise to quarantine them for a couple of weeks in a separate room. During that time, have them examined by a vet.

Some shelters or breeders will do a ringworm culture on new kittens as a precaution – you can ask about this. At the very least, monitor the new pet for any skin issues before letting them mingle. Quarantine also helps with other possible contagions (like upper respiratory viruses).

Care with outside exposure

If your cat goes outdoors or you take them to places like grooming salons or boarding facilities, be aware of the risk. It’s not to say you shouldn’t ever do these things, but just know ringworm can be picked up out there.

Wipe your cat’s paws and coat with a damp cloth when they come in from outside (especially if they were exploring soil or interacting with other animals).

Some owners use a blacklight at home to occasionally scan their cat – this isn’t a surefire method, but can sometimes catch a glowing hair early (just remember not all ringworm glows).

We’ve done this for fun in our rescue, and sometimes you do catch a suspicious little glow on an asymptomatic cat and can have it checked out.

No sharing of grooming tools between unknown animals

If you take your cat to a groomer or vet, trust that they disinfect tools (most are very good about this). At home, don’t use the same brush on a new cat that you used on another without cleaning it. In shelters or multi-animal events, avoid letting cats share items.

Routine vet care

Keep up with regular vet check-ups. Your vet might spot something on a routine exam that you missed. Also, they will ensure your cat is up to date on other preventive care, keeping them overall healthier.

There’s no regular vaccine for ringworm in pet cats (there have been vaccines in development mainly for breeding catteries, but not commonly used for house cats). So, your best defense is good care and hygiene.

If despite all precautions, you do encounter ringworm again (it can happen, especially if you foster pets or have outdoor cats), don’t blame yourself.

Ringworm spores are virtually everywhere; you can do everything “right” and still end up with an infection because of factors beyond your control. The positive side is now you’re prepared. You’ll recognize it faster and know exactly what steps to take.

We’ve had cases where someone who went through ringworm with one cat later adopts a kitten that breaks with ringworm – and they handle it like pros, catching it early and nipping it in the bud. That early detection can mean a smaller, easier-to-manage infection.

So keep an eye on your cats’ skin during grooming sessions. If you ever see a suspicious spot, you’ll know to act promptly: isolate, call the vet, and start the cleaning routine.

To wrap up, remember that ringworm is not a reflection on you or your cat’s cleanliness or care. It’s an opportunistic fungus that is part of the natural environment.

By staying informed (as you have by reading this guide), you’re empowered to deal with it effectively if it comes up. Put together, these prevention habits turn one stressful outbreak into a learning experience—which we’ll pull together for you in a short, encouraging conclusion next.

Conclusion: Bringing Your Cat Safely Through Ringworm

If you’ve read this far, you’re already doing the most important thing: you’re not ignoring the problem. You’re paying attention to your cat, you’re learning how ringworm works, and you’re planning real steps instead of panicking or waiting it out.

To bring your cat safely through ringworm, you really only need to remember a simple path:

- Spot the signs early – new bald, scaly patches or a suddenly scruffy coat are worth taking seriously.

- Let your vet confirm what’s going on – so you’re not guessing or treating the wrong skin problem.

- Follow the treatment plan all the way through – meds + baths + rechecks, even after things mira better on the surface.

- Clean in a way you can actually sustain – a realistic routine beats one “perfect” cleaning day followed by burnout.

- Protect the future – healthy skin, low stress, smarter quarantines for new pets, and regular check-ins with your vet.

Ringworm feels big and messy when you’re in the middle of it, especially if you have kids, other pets, or a multi-cat home. But it’s also finite and fixable. With consistent treatment and cleaning, most cats feel better within a few weeks and go on to live completely normal, happy lives. The fungus doesn’t change who your cat is; it’s just a temporary detour.

If you only take one thing from this guide, let it be this: you’re not a bad owner because your cat got ringworm. Spores are everywhere, even in clean homes and well-run shelters. What matters is what you do next—how quickly you notice changes, how willing you are to ask your vet for help, and how patiently you stick with the plan.

Here’s how we suggest using this guide going forward:

- Bookmark it so you can refer back to the cleaning steps and recovery timeline.

- Talk through it with your vet if you’re unsure about any part of the plan—they know your cat’s medical history and can personalize the advice.

- Share it with anyone else who handles your cat (family, pet sitter, foster coordinator), so everyone is working from the same playbook.

And if ringworm ever shows up again—on your own cat, a foster kitten, or a shelter cat you’re caring for—you’ll be ready. You’ll recognize the spots faster, set up a “sick room” more smoothly, and get ahead of the cleaning before the fungus has a chance to spread.

If you still have specific questions or “what if” scenarios on your mind, our quick Ringworm in Cats FAQ right below gives fast, skimmable answers you can refer back to anytime.

Ringworm in Cats FAQ

What is ringworm in cats?

Ringworm in cats is a fungal infection of the skin, hair, and sometimes claws. Despite the name, it’s not caused by a worm. The fungi (dermatophytes) feed on keratin in your cat’s fur and outer skin, causing circular patches of hair loss, scaling, and sometimes redness or mild itchiness.

What does ringworm look like on a cat?

Ringworm often appears as round or irregular bald patches con scaly, flaky, or slightly red skin. Common locations are the head, ears, face, paws, and tail, but lesions can appear anywhere. You might also see broken hairs, a dull coat, or mild crusting. In some cats the signs are very subtle, so regular grooming checks help.

Is ringworm in cats contagious to humans?

Yes. Ringworm is zoonosis, which means it can spread from cats to humans. People may develop a red, ring-shaped rash on the skin. Children, older adults, and anyone with a weakened immune system are more susceptible. Good hygiene, gloves when handling the infected cat, and thorough home cleaning greatly reduce this risk.

How do cats get ringworm?

Cats usually get ringworm through direct contact with an infected animal or by touching contaminated objects or environments, such as bedding, grooming tools, carpet, or furniture. The microscopic spores can survive in the environment for many months, which is why indoor-only cats can sometimes still be infected.

Can ringworm in cats go away on its own?

In a few healthy adult cats, mild ringworm might eventually improve, but we don’t recommend waiting it out. Ringworm is highly contagious and can silently spread to other pets and humans. Veterinary diagnosis and treatment are important to protect your household and to prevent the fungus from lingering in your home.

How long does ringworm treatment take?

Most ringworm cases take at least 4–6 weeks of consistent treatment. Many cats look better within 2–3 weeks, but the fungus can still be present. Vets often continue treatment until lab tests or follow-up exams confirm the fungus is gone. Stopping early is one of the most common reasons ringworm comes back.

Should I isolate my cat if they have ringworm?

Yes, if possible. Keeping your cat in a separate, easy-to-clean room helps contain the spores and makes cleaning more manageable. Provide everything they need—litter box, food, water, toys—and spend time with them using gloves and good hygiene. Isolation is temporary but dramatically reduces the risk of spreading ringworm to other pets and people.

Can other pets catch ringworm from my cat?

Yes. Ringworm can spread to other cats, dogs, and some small pets. If one animal is diagnosed, it’s wise to have other pets checked by a vet. Sometimes vets recommend treating all cats in a household, especially if there are long-haired cats, kittens, or shelter/foster animals.

Referencias

Blue Cross. (2024, September 23). Ringworm in cats – symptoms, treatment and prevention. Blue Cross Pet Advice.

Centro de Salud Felina de Cornell. (sin fecha). Ringworm: A serious but readily treatable affliction. Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Grzyb, K., DVM. (2024, April 8). Ringworm in Cats. PetMD.

Merck Veterinary Manual. (2024, Sept). Ringworm (Dermatophytosis) in Cats – Pet Owner Version. En The Merck/MSD Veterinary Manual.

Schaible, L., DVM. (n.d.). Ringworm in Cats: Symptoms, Treatment and Prevention. Hill’s Pet Nutrition.

Layne, M. (2025, July 10). What Does Ringworm Look Like on a Cat? Catster.