Introduction: Why Understanding Worms in Cats Matters

We know how unsettling the thought of “worms” in your beloved kitty can be. However, learning about these parasites is the first step to protecting your cat’s health. Worm infestations are very common – studies show that gastrointestinal parasites affect up to 45% of cats at some point. Left unchecked, worms can cause weight loss, diarrhea, vomiting, a dull coat, or that characteristic pot-bellied look in kittens.

In severe cases (especially for fragile kittens), a heavy worm burden can lead to serious anemia, intestinal blockages, or even death. Some feline worms are also zoonotic, meaning you and your family could be at risk of infection.

The good news is that worms in cats are treatable and preventable with the right approach. In this guide, we’ll share our SnuggleSouls team knowledge – from the types of worms that affect cats and how they spread, to symptoms to watch for, treatment options (both medical and natural), and practical prevention tips.

Our goal is to help you keep your furry friend worm-free, healthy, and happy. Let’s dive in!

What Are Worms in Cats? (Definition and Types)

“Worms” in cats are intestinal or organ parasites – slender, often thread-like creatures that live inside a cat’s body, stealing nutrients or blood from their host. (Don’t confuse them with ringworm, which is actually a skin fungus, not an actual worm.)

Cat worms come in many forms and sizes. Below we define the most common types of worms in cats and what makes each unique:

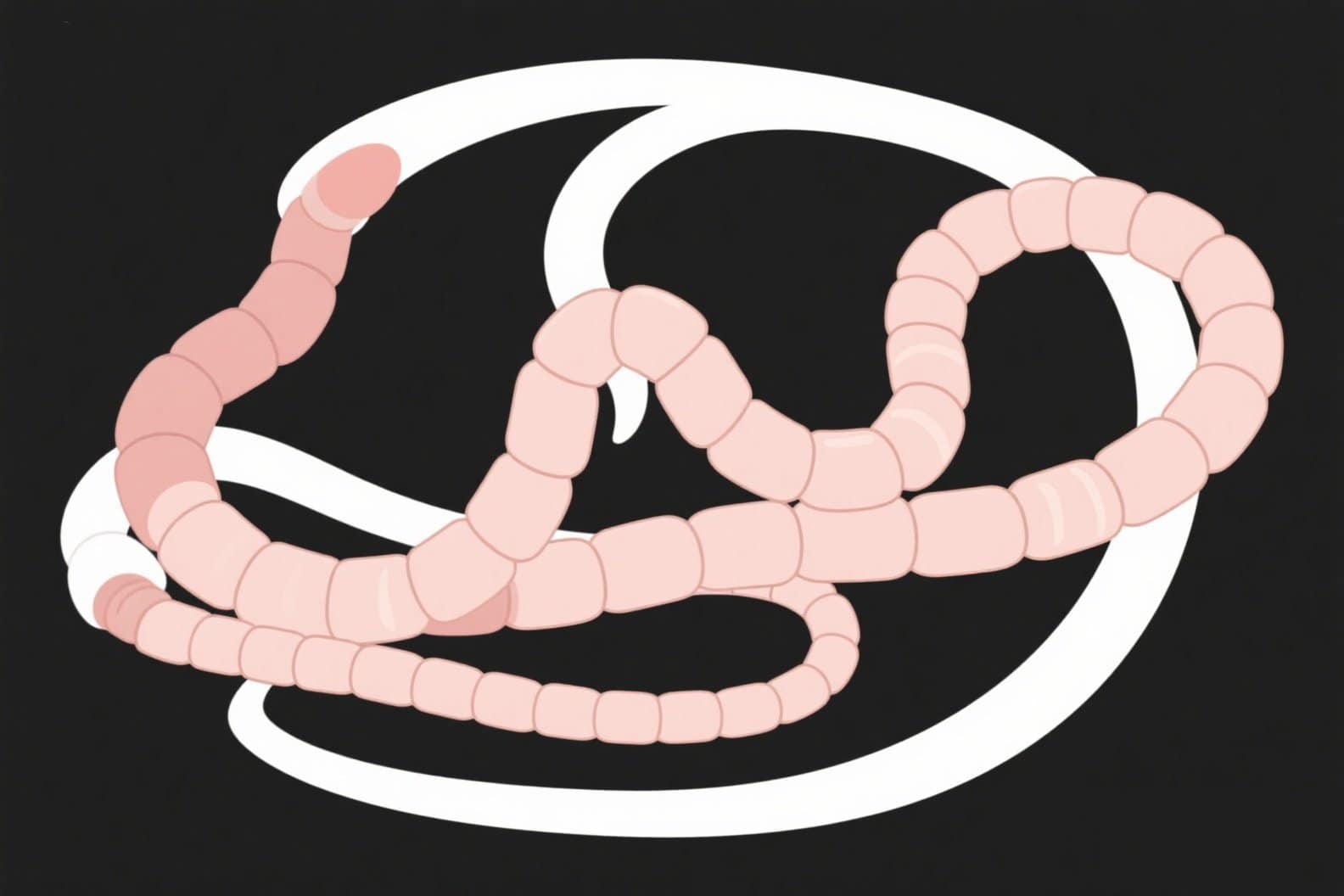

Roundworms (Ascarids)

The most common intestinal worms in cats. Roundworms are long (3–5 inches), spaghetti-like creamy-white worms that live in the small intestine. They produce microscopic eggs that pass in the cat’s feces.

Kittens are especially prone to roundworms, often catching them from their mother. In fact, Toxocara cati (a common roundworm) can be transmitted through an infected mother cat’s milk to nursing kittens. Adult cats can ingest roundworm eggs from a contaminated environment or by eating infected prey (like rodents or birds).

These worms rob nutrients, so heavy infections can cause a pot-bellied appearance, stunted growth, and digestive upset in young cats.

Hookworms

Much smaller than roundworms (often less than ½-inch long and very thin), hookworms latch onto the lining of the intestines with hook-like mouthparts and suck blood. They are less common in cats than roundworms, but can be very dangerous because of their blood-drinking habits.

Cats can catch hookworms by ingesting infective larvae (for example, grooming contaminated dirt off their paws) or even via larvae penetrating the skin (often through the paws).

Hookworms can live a long time in a cat’s body and cause bleeding into the intestines – leading to dark, tarry diarrhea, weight loss, weakness, and life-threatening anemia in severe cases. (Pale gums in a cat are a red-flag sign of hookworm anemia.)

Fortunately, these worms are only a few millimeters in size and not usually visible in feces.

Tapeworms

Flat, ribbon-like worms made up of many segments. Tapeworms are quite common and tend to be noticed when they shed segments. Owners often find rice-grain-like cream-colored segments stuck to the fur under the tail or in the cat’s bedding. Each segment is essentially a packet of tapeworm eggs.

The most common tapeworm in cats (Dipylidium caninum) is acquired through ingesting an infected flea during grooming. Cats can also get other tapeworms (e.g. Taenia species) by eating infected rodents or rabbits.

Tapeworms anchor into the small intestine and can grow very long, but they usually cause mild clinical effects (maybe slight weight loss or digestive upset).

Often, the biggest nuisance is seeing the wriggling segments. However, a heavy tapeworm infestation can irritate a cat’s anus (causing scooting) and occasionally cause vomiting or intestinal blockage if untreated. Modern dewormers easily kill tapeworms, but reinfection is common if fleas aren’t controlled.

Whipworms

Whipworms are uncommon in cats (more often a dog parasite). As their name implies, they have a whip-like shape (thicker at one end, very thin at the other) and reside in the cecum/large intestine.

Cats pick up whipworms by ingesting infective eggs from soil or feces. In light infections, cats may show no symptoms at all; heavier infections can cause diarrhea (sometimes with blood or mucus), weight loss, and general poor condition.

The good news is whipworms in cats are rare and usually not as severe as some other worms. Still, if present, they should be treated to relieve any discomfort and prevent spread.

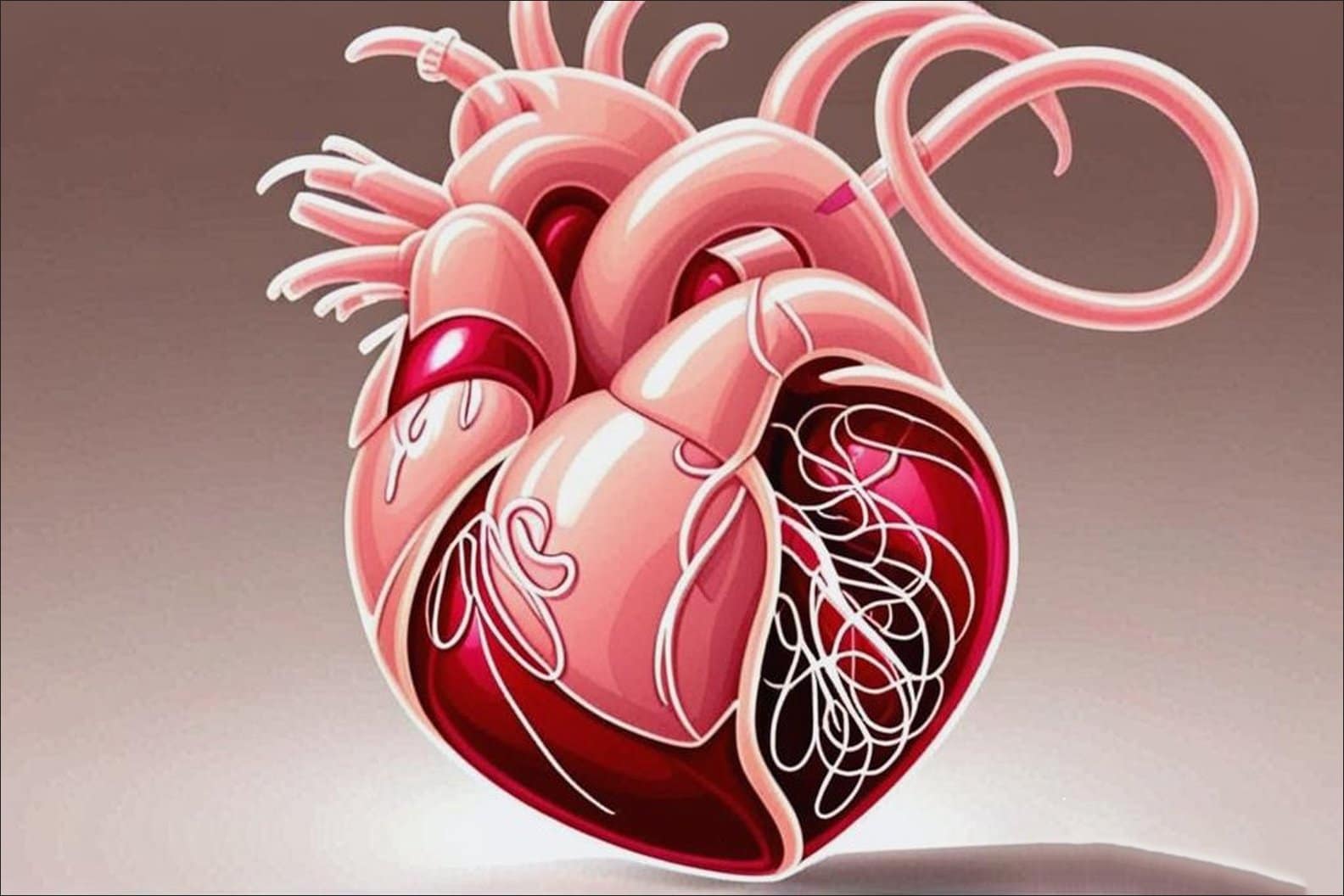

Heartworms

Unlike the intestinal worms above, heartworms live in a cat’s heart and lungs. Heartworm disease in cats is less common than in dogs, but it is an especially serious infection.

Cats become infected when bitten by a mosquito carrying heartworm larvae – the tiny larvae migrate through the cat’s tissues and develop into adult worms within the blood vessels of the heart and lungs.

Even a single heartworm can be dangerous for a cat, causing severe lung inflammation and respiratory issues.

Cats are at risk even if they live indoors (mosquitoes can get inside). Unfortunately, there is no safe drug to eliminate adult heartworms in cats – which makes prevention critical. We’ll discuss heartworms more later (symptoms, etc.), but it’s important to include them in any list of feline worms due to the gravity of infection.

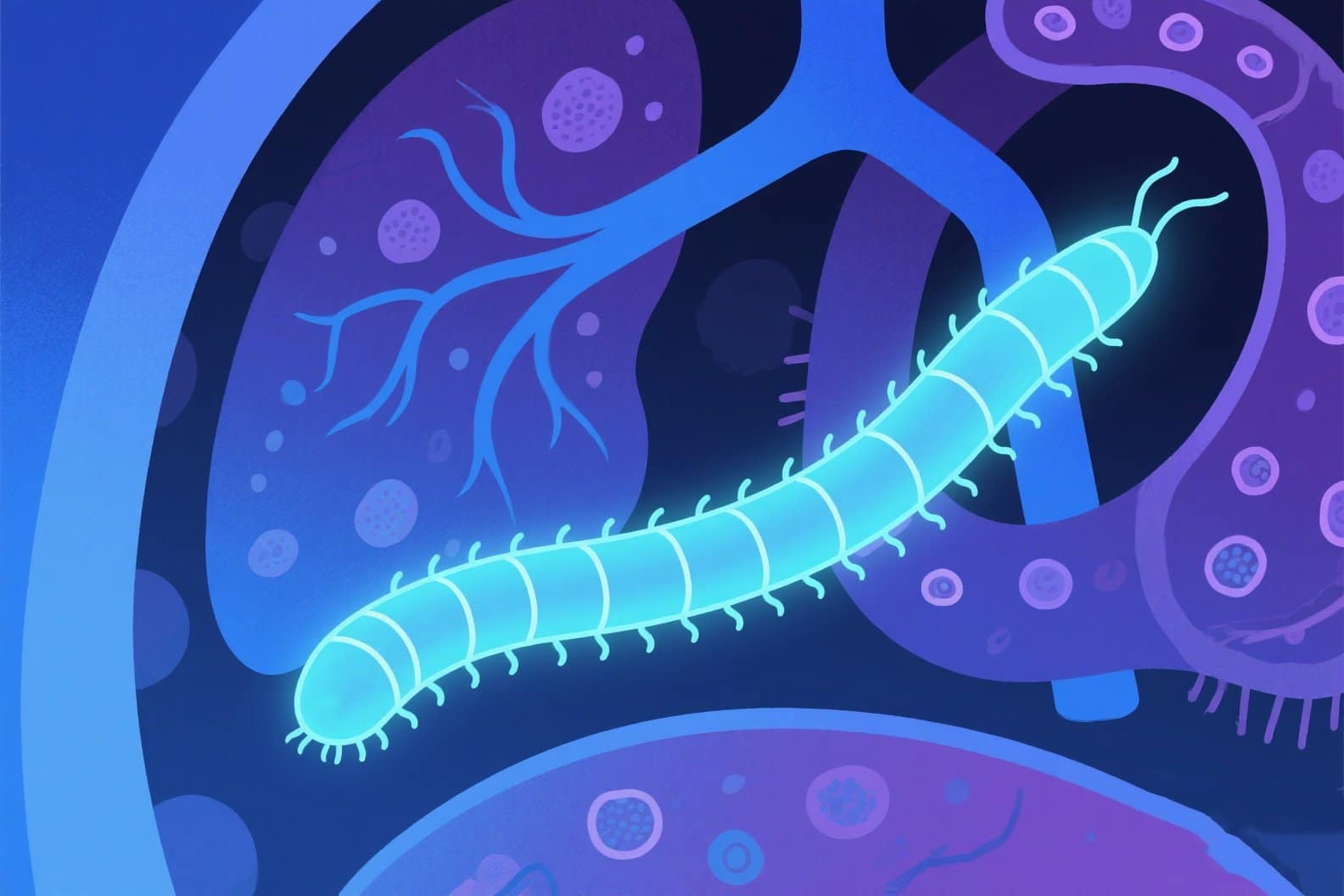

Lungworms

Lungworms are parasitic worms (such as Aelurostrongylus abstrusus) that settle in a cat’s lungs or airways, rather than the gut. Cats typically get lungworms by eating a small animal that carries infective larvae – for example, snails or slugs (intermediate hosts) or rodents, birds, or lizards that ate those snails.

Once swallowed, the larvae migrate to the lungs and mature there. Lungworm infection can cause coughing, wheezing, difficulty breathing, and can progress to pneumonia in heavy infections.

Many cats show only mild signs, but in kittens or immunosuppressed cats, lungworms can be serious. Diagnosis requires specialized tests (finding larvae in feces or airway fluid), and treatment often involves specific dewormers (different from standard intestinal worm meds).

Other parasites

In addition to the above, cats can occasionally be affected by stomach worms (like Physaloptera or Ollanulus – causing vomiting), bladder worms (which live in the urinary bladder), or liver flukes (flatworms that invade the liver/gallbladder, usually from eating infected frogs, lizards, or fish).

These are fairly rare and usually occur in specific circumstances (for example, liver flukes in cats are seen in certain tropical areas).

Also, keep in mind there are many non-worm parasites (like Giardia, Coccidia, and Toxoplasma) that can infect cats – those are protozoa (single-celled organisms), not “worms,” but they can cause similar gastrointestinal issues.

For this article, we will focus on actual worms (helminths), as listed above.

To help summarize the different worm types, their transmission, and effects, here’s a quick comparison.

| Worm Type | How Cats Get It | Key Symptoms/Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Roundworms (Toxocara, Toxascaris) | Ingesting eggs from contaminated soil or feces; nursing from an infected mother’s milk; eating infected prey (rodents, birds). | Pot-bellied belly (especially in kittens), diarrhea, vomiting, weight loss, dull coat; worms may be visible in stool or vomit. Heavy infestations can block intestines. |

| Hookworms (Ancylostoma, Uncinaria) | Larvae from contaminated soil penetrate the cat’s skin (often paw pads); or cat ingests larvae (e.g. during grooming). Possibly via mother’s milk (if queen is infected). | Often no visible worms in stool (they’re tiny). Causes blood loss – signs include black/tarry diarrhea, anemia (pale gums), weakness, and weight loss. Severe hookworm infestations can be fatal in kittens due to anemia. May cause itchy skin lesions where larvae entered. |

| Tapeworms (Dipylidium, Taenia, etc.) | Ingesting an intermediate host: usually infected fleas (Dipylidium) during grooming, or eating infected small animals (rodents, rabbits) that carry tapeworm cysts. | Mild digestive upset or no symptoms in many cases. Telltale sign is rice-like segments around anus or in feces, causing itching or scooting. Possible weight loss or increased appetite. Rarely, a heavy tapeworm burden can cause vomiting or intestinal blockage. |

| Whipworms (Trichuris) | Ingesting eggs from contaminated soil, water, or feces. (Whipworm eggs are hardy in the environment.) | Often asymptomatic when few worms. Larger infestations can cause colitis – chronic diarrhea (with mucus or blood), weight loss, dehydration. (Whipworms are rare in cats; more common in dogs.) |

| Heartworms (Dirofilaria) | Bite of an infected mosquito – transmits larvae into the cat’s bloodstream. Cats are not natural hosts, but can still get heartworms anywhere mosquitoes are present. | Coughing and breathing difficulty (sometimes mistaken for asthma); lethargy; weight loss; vomiting. Sudden collapse or sudden death can occur in cats with heartworm (even with few worms). Heartworms primarily damage the lungs and heart. (There is no easy cure in cats – prevention is key.) |

| Lungworms (Aelurostrongylus & others) | Eating animals that contain larvae (snails, slugs, or prey like birds/rodents that ate snails). Larvae migrate from intestines to lungs. | Coughing, wheezing, difficulty breathing – from lung inflammation. In heavy infections, can progress to pneumonia (cats may show rapid breathing or open-mouth breathing). Mild cases might have no obvious symptoms at all. |

Note: There are other less-common worms (stomach worms, bladder worms, liver flukes, etc.) and many microscopic parasites that infect cats, but the ones above are the major “worms” cat owners should know about. Now that we know what we’re dealing with, let’s see how cats contract these pesky critters in the first place.

How Do Cats Get Worms?

Cats can get worms through several transmission routes. Understanding these will help you prevent new infections. Here are the major ways cats contract worms:

Ingestion of Worm Eggs or Larvae from the Environment

Cats are fastidious groomers – if your cat walks through a patch of soil or litter contaminated with microscopic worm eggs, they may lick the particles off their fur and swallow the eggs.

Contaminated soil is a common source of roundworms and hookworms. For example, roundworm eggs passed in an infected animal’s feces can survive in dirt for months to years. A cat digging or walking in a garden bed, then licking their paws, can ingest those eggs without anyone knowing.

Similarly, hookworm larvae in damp sand or soil can even burrow directly into a cat’s skin (usually through the soft skin between the toes). This is why even strictly outdoor soil or communal litter areas can pose a risk.

Regularly cleaning the litter box and preventing cats from roaming in areas with unknown feces can cut down this risk.

Hunting and Eating Prey

Has your cat ever brought you a “gift” of a mouse or bird? Hunting is a natural cat behavior – unfortunately, it’s also a classic way cats get worms. Many small mammals (mice, rats, squirrels) and birds can act as intermediate hosts carrying dormant stages of worms.

When a cat eats an infected prey animal (or even just consumes part of a carcass), they can acquire tapeworms, roundworms, or lungworms in the process.

For instance, rodents commonly harbor roundworm larvae in their tissues; a hunting cat that eats the mouse will then get the roundworms.

This is a major route of infection for outdoor cats or any cat with access to hunting. Even indoor cats aren’t 100% safe – if an unlucky mouse finds its way into your house and your cat catches it, that single event could transmit worms.

Fleas (Grooming Ingests Fleas)

Fleas are more than just an itchy annoyance – they can carry tapeworm larvae. Cats get tapeworms by swallowing infected fleas during grooming.

Here’s the cycle: flea larvae in the environment ingest tapeworm eggs; those fleas mature and hop onto your cat; your cat then grooms, bites, or scratches and inadvertently swallows a flea – and voilà, the tapeworm larva is now inside the cat and grows into an adult tapeworm.

This is the most common way indoor-only cats get worms, because fleas can hitchhike into even the cleanest homes (on people’s clothing or other pets).

If you’ve ever seen your cat nibble at an itchy spot and chew up a flea, that’s a potential tapeworm exposure. Effective flea control is thus critical to prevent tapeworm infections.

Mother’s Milk or in Utero

Kittens can be born with worms or get them very early in life through their mother. If a mother cat has had roundworms or hookworms, dormant larvae can activate during pregnancy and infect her kittens.

Roundworm larvae commonly migrate to the mammary glands, so nursing kittens ingest the larvae through the mother’s milk. Hookworm larvae can also pass in milk or even across the placenta before birth in some cases.

This is why virtually all young kittens (even from seemingly healthy indoor mothers) are assumed to have roundworms – most breeders and veterinarians deworm kittens proactively starting at 2-3 weeks old.

If you’ve adopted a young kitten, it likely has been (or needs to be) dewormed for this very reason. Mother-to-kitten transmission is a significant route, and it underscores how important it is to deworm pregnant/nursing mother cats under vet guidance so the kittens start life with fewer parasites.

Mosquito Bites

As mentioned earlier with heartworms, mosquitoes transmit heartworm larvae. When a mosquito bites an infected animal (like a dog or coyote with microfilariae in its blood) and then bites your cat, it can inject heartworm larvae.

Cats that live in regions where heartworm is present (many warm or humid climates) are at risk, even if they never go outside – a single mosquito in the house is all it takes.

Heartworm infection does not spread from cat to cat or from dogs to cats directly; only mosquitoes carry the larvae.

This is a different route than the fecal/oral cycle of intestinal worms, but it’s crucial to remember for prevention (using heartworm prevention medications and mosquito control in endemic areas).

Contact with Other Animals or Feces

Cats can catch worms by encountering the feces of other infected animals. For example, if an outdoor cat uses a garden as a toilet, and later your cat sniffs or steps in that spot, they could pick up worm eggs.

Dogs and cats can share certain worms, too – e.g. cats can get certain roundworms or hookworms from dog feces in the yard. (On the flip side, some cat parasites like Toxocara cati can potentially infect dogs if ingested, though dogs mainly get their own species Toxocara canis.)

Sharing litter boxes in multi-cat homes can also spread worms if one cat is shedding eggs. Generally, any scenario where a cat comes into contact with infected fecal matter or vomit from another animal poses a risk.

This is why scooping the litter box daily and discouraging cats from investigating other animals’ droppings is so important in worm prevention.

Fleas, Roaches, and Other “Intermediate” Hosts

We mentioned fleas specifically for tapeworm, but cats are curious creatures and sometimes eat things that carry parasites indirectly. For instance, cockroaches can ingest roundworm eggs and act as transport hosts – a cat that catches and crunches a cockroach could get roundworms that way.

Beetles can harbor Physaloptera (stomach worm) larvae. Slugs/snails carry lungworm larvae. Even indoor cats can occasionally catch insects (like a moth or roach) that might harbor parasite eggs/larvae.

The risk from insects is lower than from fleas or rodents, but it exists. Good household pest control can further reduce your cat’s parasite exposure.

Recognizing the Signs: Symptoms of Worms in Cats

If you suspect your cat might have worms, the first thing we encourage is gentle observation—paired with a proactive vet visit. Many cats don’t show dramatic signs of a worm infection at first. That’s exactly why early detection is often missed.

Some of the most common signs include:

Visible worms or worm segments, often in stool, vomit, or near the tail (especially tapeworms and roundworms).

Pot-bellied appearance, especially in kittens with roundworms.

Appetite changes and unexplained weight loss, due to nutrient theft by parasites.

Vomiting or diarrhea, sometimes with mucus or blood, depending on worm type.

Coughing or breathing issues, caused by migrating larvae or lungworm infections.

Scooting or excessive licking at the rear, often a sign of anal irritation from tapeworms.

Pale gums and lethargy, which may signal anemia from blood-feeding worms like hookworms.

Coat and skin changes, including dryness, flaking, or a general unkempt look.

What makes things harder is that these symptoms can overlap with many other feline health issues. But when they occur in clusters—or persist despite changes in food or routine—it’s time to consider parasites.

If you’re unsure how to connect symptoms to specific types of worms—or wondering whether your indoor-only cat could even have parasites—we’ve written a complete guide just for you. It breaks down each symptom, what it likely means, and when to act.

👉 Read the full guide: Symptoms of Worms in Cats: 9 Warning Signs to Know

Because when your cat’s body is no longer fighting hidden invaders, they can finally return to being their vibrant, comfortable self again.

How Worms Are Treated: Deworming Strategies That Actually Work

When your cat is diagnosed with worms—or even if there’s just strong suspicion based on symptoms—it’s not a reason to panic. Modern deworming methods are safe, highly effective, and surprisingly manageable. But they’re not one-size-fits-all.

The right medication depends on the type of parasite, the age and health status of your cat, and sometimes even your home environment.

Here’s what you need to know:

· Veterinary dewormers are the gold standard. Products containing pyrantel pamoate or fenbendazole are commonly used for roundworms and hookworms. For tapeworms, medications like praziquantel are the go-to solution.

· Different worms require different treatments. Heartworms, for instance, have no direct cure in cats—treatment focuses on symptom relief and prevention.

· Follow-up matters. Many medications require repeat doses or follow-up fecal tests to confirm success.

· Natural remedies? Options like pumpkin seeds or food-grade diatomaceous earth may offer mild benefits as supplements—but shouldn’t replace professional treatment.

· Environmental care is part of the process. Cleaning your home, washing bedding, and treating fleas (if present) are crucial steps to prevent reinfection.

The takeaway: Deworming is more than a one-pill solution—it’s a strategic, tailored process. And when done properly, it doesn’t just eliminate parasites—it restores your cat’s vitality and protects everyone in your home.

For an in-depth guide on the safest, most effective treatment options and how to prevent it, check out our full blog post:

👉Cat Deworming Strategies: How to Treat and Prevent Worms

Conclusion

Dealing with worms in your cat can feel overwhelming or downright icky – we get it! But the key takeaway is one of empowerment and optimism: with the right knowledge and care routine, you can protect your cat and quickly get rid of any worms that pop up.

At SnuggleSouls, we have seen countless cats recover fully from worm infestations and go on to live healthy, happy lives.

The journey usually goes like this: you notice something (maybe some rice-like specks or a pot-bellied tummy), you get a diagnosis (vet confirms worms), you treat the cat (a few doses of dewormer, maybe some cleaning), and voilà – your feline friend is feeling frisky and worm-free again.

Lastly, we want to reassure you: if your cat does get worms, don’t panic. Now you have the knowledge to handle it. Your cat can’t tell you “Hey, I’ve got a tummy full of worms,” but with the information from this article, you’ll be able to spot the clues and take action. And of course, your veterinarian is your ally – never hesitate to call them with concerns about parasites or any aspect of your pet’s health.

They’ve truly “seen it all” when it comes to worms, and they’re there to help, not to judge.

At SnuggleSouls, our mission is to help you give your cat the best life possible. Keeping them worm-free is a big part of ensuring they feel their best. With vigilance and care, you can snuggle your soul (and your cat) knowing that those pesky worms don’t stand a chance. Here’s to your cat’s good health and many happy, parasite-free adventures together!

FAQ

Can worms in cats go away on their own?

No, most worms won’t go away without treatment. They can persist, reproduce, and cause health issues unless addressed with proper deworming medication.

Do indoor cats really need deworming?

Yes! Even indoor cats can get worms from fleas, mosquitoes, insects, or contaminated soil brought in by humans or other pets.

How often should I deworm my cat?

Kittens need deworming every 2–3 weeks early on. Adult cats should be dewormed every 3 months if high-risk, or at least yearly for indoor-only cats. Ask your vet for a tailored plan.

What are the signs my cat might have worms?

Symptoms include visible worms in stool or vomit, bloated belly, weight loss, diarrhea, dull coat, and scooting. But some cats show no signs, so regular testing is key.

Can I treat my cat’s worms at home?

OTC and natural remedies may help mild cases, but the safest and most effective treatment is vet-prescribed dewormers, especially for identifying the right worm type.

References

Sweet, S., Szlosek, D., McCrann, D., Coyne, M., Kincaid, D., & Hegarty, E. (2020). Retrospective analysis of feline intestinal parasites: trends in testing positivity by age, USA geographical region and reason for veterinary visit. Parasites & Vectors, 13(1), 473. https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-020-04319-4

Gómez, M., et al. (2021). Toxocara cati and other parasitic enteropathogens: More commonly found in cats with digestive clinical signs. Pathogens, 10(2), 198. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/10/2/198

Khelifi, M., et al. (2022). Gastrointestinal parasites in domestic cat (Felis catus): Prevalence and risk factors. South Asian Journal of Experimental Biology, 12(2), 567. https://sajeb.org/index.php/sajeb/article/view/567sajeb.org

Zhou, X., et al. (2025). Gastrointestinal protozoa in pet cats from Anhui province: Prevalence and zoonotic potential. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 15, 1522176. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-and-infection-microbiology/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2025.1522176/full

Lappin, M. R., et al. (2021). Parasites in the gastrointestinal system of dogs and cats. In Veterinary Parasitology (pp. 1-20). Elsevier. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323953528000011