Table of Contents

Quick answer: Most female cats stay in heat (estrus) about 5–7 days, but it can last as short as 3 days or as long as 14 days.

If she doesn’t mate, heat can return every 2–3 weeks during breeding season.

If you’re not breeding your cat, spaying is the only reliable way to stop heat cycles long-term.

If you’re wondering how long cat heat lasts, you’re probably dealing with the yowling, pacing, and nonstop affection right now.

This guide gives you the exact timeline (including how long each stage lasts), the 8 clearest signs, and what actually helps at home—plus when spaying is the best option.

Cat Heat Cycle Timeline (Stages + How Long Each Lasts)

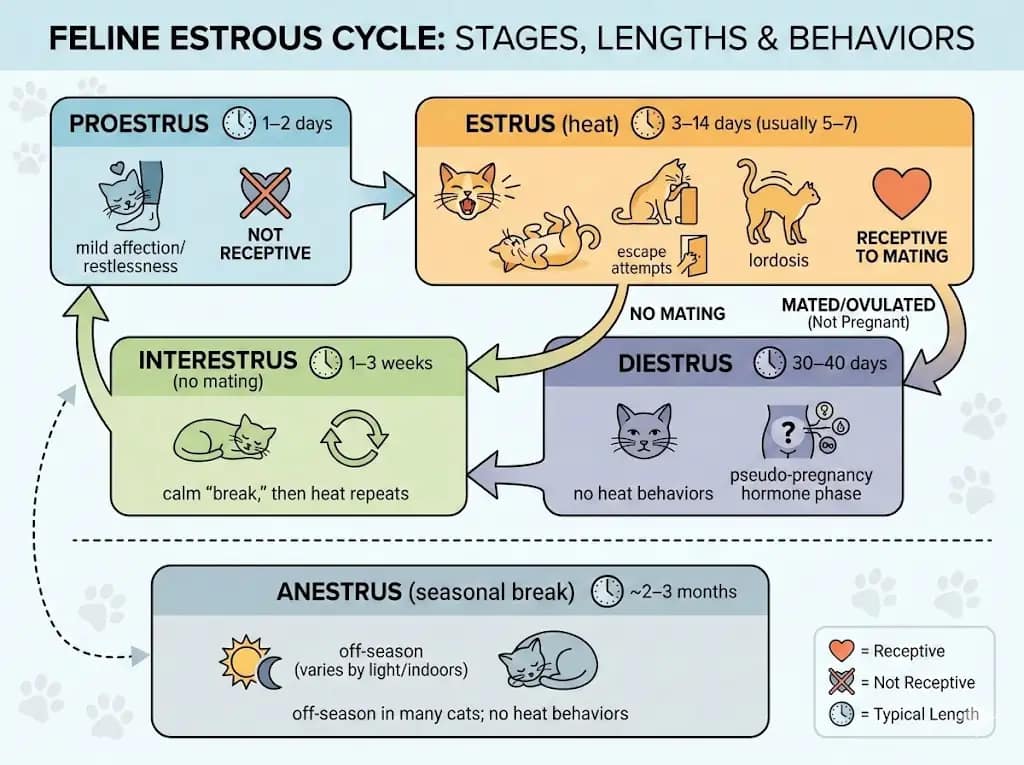

The feline estrous cycle consists of four main phases (proestrus, estrus, interestrus/diestrus, and anestrus). Proestrus and estrus together make up the “heat” period when your cat is fertile, whereas interestrus (or diestrus) and anestrus are phases with little to no mating activity.

A female cat’s reproductive cycle is called the estrous cycle, commonly known as the “heat” cycle. Cats are seasonally polyestrous, meaning they can go into heat multiple times during their active breeding season.

In the Northern Hemisphere, that usually means cycling from around January through late fall, and taking a break in winter. (If you live in a tropical climate or keep your cat primarily indoors under constant light, she might cycle year-round without a winter break.)

So, how long does each heat last, and what does the timeline look like? Here’s a breakdown of the typical cycle phases your cat will experience:

| Stage | Typical length | What you’ll notice |

|---|---|---|

| Proestrus | 1–2 days | mild affection/restlessness; not receptive |

| Estrus (heat) | 3–14 days (usually 5–7) | yowling, rolling, rubbing, lordosis, escape attempts |

| Interestrus (no mating) | 1–3 weeks | calm “break,” then heat repeats |

| Diestrus (mated/ovulated, not pregnant) | 30–40 days | no heat behaviors; “pseudo-pregnancy” hormone phase |

| Anestrus (seasonal break) | ~2–3 months | off-season in many cats (varies by light/indoors) |

Key takeaway: Your cat is “in heat” only during estrus, which usually lasts about a week, but can stretch up to two weeks. If she doesn’t mate, it often repeats every 2–3 weeks in breeding season.

Proestrus (about 1–2 days)

Length: ~1–2 days

What’s happening: Estrogen starts rising and your cat’s body is gearing up for estrus.

What you’ll notice: Mild changes—slightly more affectionate, restless, or “off,” but many cats show very subtle signs.

Owner tip: Male cats may show interest, but she usually isn’t receptive yet—don’t assume the loud yowling stage has started.

Estrus (heat) (about 3–14 days)

Length: 3–14 days (most commonly 5–7 days)

What’s happening: This is the true “heat” phase when she’s fertile and actively seeking a mate.

What you’ll notice: Loud yowling (often day and night), intense rubbing/rolling, restlessness, escape attempts, and the mating stance (hindquarters raised, tail to the side).

Owner tip: She’s usually not in pain—it’s hormonal drive. Keep her strictly indoors; mating can happen very fast.

Why it varies: duration depends on the individual cat, season/light exposure, and whether she mates/ovulates.

Between Heats – Interestrus vs. Diestrus

If she does not mate: Interestrus (about 1–3 weeks)

Length: ~1–3 weeks

What’s happening: Heat behaviors stop temporarily, but the cycle resets and can start again soon.

What you’ll notice: She acts mostly normal again—quieter, calmer, less restless.

Owner tip: This “break” can be short. Many cats return to heat again within a couple of weeks during breeding season.

If she mates and ovulates (but isn’t pregnant): Diestrus (about 30–40 days)

Length: ~30–40 days

What’s happening: After ovulation, hormones shift into a “pseudo-pregnancy” phase even if she doesn’t conceive.

What you’ll notice: Heat behaviors usually disappear during this time.

Owner tip: No heat signs doesn’t automatically mean she isn’t pregnant—if mating happened, consider a vet check.

Anestrus (seasonal “off” period) (about 2–3 months)

Length: ~2–3 months (varies a lot)

What’s happening: Many cats pause cycling during shorter-daylight months; reproductive activity drops.

What you’ll notice: No heat behaviors—no yowling, no mating stance, no roaming urgency.

Owner tip: Indoor cats under constant lighting may have no clear off-season and can cycle year-round.

Key takeaway

Your cat is “in heat” only during estrus, which usually lasts ~5–7 days (range 3–14).

If she doesn’t mate, heat often returns every 2–3 weeks in breeding season.

The cycle repeats until she becomes pregnant—or you stop it through spaying.

What Affects How Long a Cat Stays in Heat?

Cats don’t all follow the same schedule. Two cats can be in heat for very different lengths of time—even if both are healthy. Here are the biggest factors that influence how long heat lasts and how often it returns.

1. Age and “First Heat” Irregularity

First heat cycles (especially in younger cats) can be a bit unpredictable.

Some cats show milder signs at first, while others seem “in heat forever” because the behaviors blur together across early cycles.

Content note (SEO-friendly): This helps you rank for “how long is a cat in heat the first time?” and “why is my kitten in heat so long?”

2. Season and Daylight (Breeding Season vs Off-Season)

Cats are strongly influenced by day length. Longer days generally trigger more cycling.

During peak season, heat cycles can feel relentless because the “break” between heats may be short.

Add a 1-line clarifier:

If it’s spring/summer and your cat is unspayed, frequent heats are often normal.

3. Indoor Lighting (Year-Round Heats)

Indoor cats exposed to consistent artificial light may cycle more often and may not have a clear off-season.

That can make heat appear to last longer, when it’s actually short cycles repeating with short breaks.

Optional mini-tip (keep it mild):

Some owners find a darker, calmer room reduces stimulation, but it won’t stop the cycle entirely.

4. Whether Mating/Ovulation Occurs

Cats are induced ovulators, meaning ovulation typically happens after mating.

If your cat doesn’t ovulate, she may return to heat sooner.

If she does ovulate (even without pregnancy), she may enter a longer “quiet phase.”

Why this matters: This explains “why did she stop… then start again?” patterns.

5. Stress, Environment, and Household Triggers

Heat behaviors often look “worse” (and feel longer) when your cat is:

Hearing/smelling outdoor cats nearby

Living with an intact male (even separated)

Under stress (new home, new pets, routine disruptions)

Important framing:

These factors usually don’t change the biology of heat, but they can make the behaviors more intense or continuous.

6. Health Reasons That Can Mimic “Endless Heat” (When to Call a Vet)

Most prolonged heat is just variation—but it’s smart to watch for red flags.

Contact a vet if:

Heat-like behavior continues beyond ~14 days

You see blood, foul-smelling discharge, or pus-like discharge

Your cat is lethargic, vomiting, hiding, or refusing food for more than a day

The abdomen looks swollen, or she seems painful

Rule of thumb: Loud, needy behavior is common in heat. Signs of illness are not.

Quick summary

Heat length varies most because of age, season/daylight, indoor lighting, and whether ovulation occurs. If heat behavior seems to last longer than two weeks, or your cat seems unwell, it’s time to check in with a vet.

How Often Do Cats Go Into Heat?

During breeding season, many unspayed female cats go into heat about every 2–3 weeks if they don’t get pregnant. That means once one heat ends, another can start again in as little as 1–2 weeks.

During the winter (short days)

This is the anestrus phase we mentioned, lasting a couple of months with no cycling. However, not all cats read the textbook – some indoor cats under constant indoor lighting may skip the winter break and continue to cycle year-round.

Additionally, certain breeds (like Siamese or other oriental breeds) are well-known for having frequent or early heat cycles, whereas some other breeds might cycle a bit later or less intensely. Individual variation is huge.

To put it in perspective, if unspayed, a single female cat could go into heat up to a dozen times or more in one year (especially if she doesn’t get a winter rest). That’s a lot of hormonal rollercoasters for both cat and owner!

This is one reason managing an unspayed cat can be challenging – it’s not a once-in-a-while event, but a frequent fact of life.

Bottom line: Cats can go into heat repeatedly throughout most of the year. If your kitten has her first heat in the spring and you don’t spay her, be prepared for many rounds of flirtatious theatrics in the months ahead. Knowing this, it becomes even more important to recognize the signs of heat and have a plan for handling each cycle (or better yet, preventing them, which we’ll discuss soon).

At a glance: Heat every 2–3 weeks (breeding season), with some indoor cats cycling year-round.

Recognizing the Signs: How to Tell If Your Cat Is in Heat

If you’re suddenly hearing your cat cry out in strange ways or rubbing herself on everything in sight, you might be wondering: Is she just being weird—or is she in heat?

The good news (and sometimes the challenging news) is that when a female cat enters estrus, her behavior usually makes it pretty clear.

Here’s what to look for:

Nonstop Vocalizing

One of the loudest giveaways is loud, persistent meowing or howling—often at night. These aren’t her usual chatty meows. They’re deep, drawn-out, and unmistakably intense. This is her way of calling for a mate, and it can sound like she’s in pain (don’t worry—she’s not).

Clingy and Affectionate—Sometimes to the Extreme

Suddenly, your normally independent cat may be glued to your side. She’ll rub against your legs, furniture, walls—anything—and might roll around, demand attention, and purr endlessly. Even shy cats can become bold and needy during heat.

The Mating Stance (Lordosis)

When stroked along her back, a cat in heat may drop her front half, raise her rear, hold her tail to one side, and tread with her hind paws. This pose signals mating readiness. It can also happen spontaneously as she walks or stretches.

Restlessness and Roaming Behavior

Expect pacing, peering out windows, and loitering around doors. Your cat may seem antsy and “on a mission”—she’s trying to find a way to meet a male.

Escape Attempts

Queens in heat are escape artists. Doors, windows, even slightly ajar cabinets—nothing is safe. If she gets out, male cats will find her. It only takes one moment for an unwanted pregnancy to happen.

Loss of Appetite

Some cats eat less during heat. If she’s otherwise active and showing other estrus behaviors, a temporary dip in appetite is normal. Just make sure she resumes normal eating after her cycle ends.

Spraying or Urine Marking

Some females spray vertical surfaces or urinate more often. This isn’t bad manners—it’s biology. Her urine is rich with hormones and pheromones, a message to local tomcats that she’s fertile.

Increased Grooming of the Genital Area

You might notice her licking this area more. Slight swelling or clear discharge can be normal. However, blood is not—if you see any, contact your vet.

We’ve put together a full behavioral breakdown to help you decode each of these estrus signals—and how to respond.

Read the complete guide: Signs Your Cat Is in Heat: 8 Clear Behaviors to Know

What To Do When Your Cat Is in Heat (Care Tips That Actually Help)

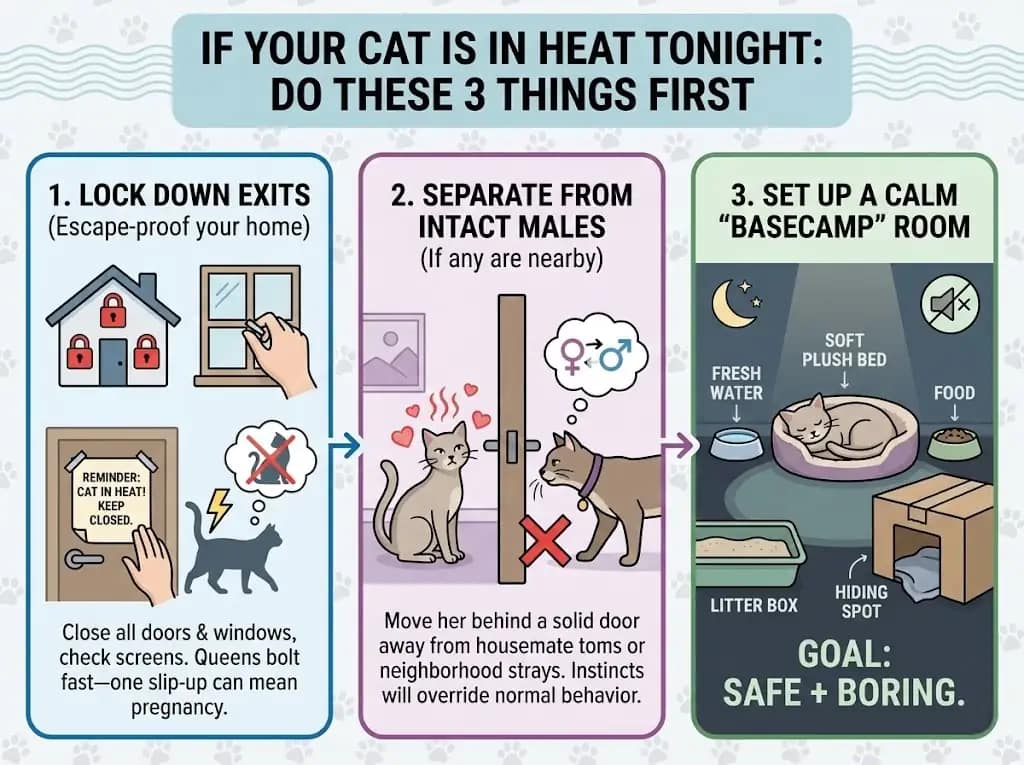

If your cat is in heat right now, treat the first hour like “damage control.” Your main goal is simple: prevent escape and calm the environment. Once that’s handled, you can focus on comfort for the next several days.

If your cat is in heat tonight: do these 3 things first

Lock down exits (escape-proof your home).

Close all doors and windows, check screens, and put a reminder note by entryways. Queens in heat can bolt fast—one slip-up can mean pregnancy.Separate her from intact males (if any are nearby).

If you live with an unneutered male cat—or if neighborhood toms hang around—move her to a room with a solid door. Even cats that normally get along will follow instincts.Set up a calm “basecamp” room.

Give her a quiet space with: fresh water, food, a clean litter box, soft bedding, and a hiding spot. Keep lights low and noise minimal—your goal is “safe + boring.”

Once you’ve done those three steps, use the tips below to make the rest of her heat cycle more manageable for both of you.

1. Keep the lockdown consistent (especially at doors).

You’ve already secured exits—now make it routine. Use a quick “door check” habit, and ask family members to pause before opening doors. If tomcats are outside, don’t leave windows open even with screens if they’re weak or loose.

2. Make her basecamp extra comforting.

Add a warm blanket or towel, and keep the room low-stimulation. Some cats relax with a covered bed or a box. The goal is “safe, quiet, predictable.”

3. Use short play bursts to burn off restless energy.

Even in heat, many cats will engage in short sessions. Try feather toys or a wand toy for 5–10 minutes, then let her rest. A little activity often reduces pacing later.

4. Offer affection—but let her control the dose.

If she seeks contact, give gentle strokes or brushing. If she gets overstimulated or walks away, don’t chase the interaction. Heat can make cats clingy one moment and sensitive the next.

5. Try calming aids (low-risk first).

A pheromone diffuser (like Feliway-style products) can take the edge off for some cats. If you’re considering supplements, choose cat-specific options and follow label directions. Skip essential oils—many aren’t cat-safe.

6. Keep the litter box spotless (and add a second box if needed).

Heat can increase urination or lead to spraying. Scoop more frequently, and if she’s confined to one room, an extra box can prevent accidents.

7. Clean marking with enzyme cleaner—fast.

If she sprays, clean it immediately with an enzyme-based cleaner so the scent doesn’t invite repeat marking. Avoid ammonia-based cleaners—they can smell like urine to cats.

8. Protect your sleep and your bond (no punishment).

Use white noise or move her basecamp away from bedrooms overnight if possible. Don’t scold heat behavior—she’s not misbehaving; she’s hormonally driven. Calm redirection works better than confrontation.

These strategies can make heat less intense, but they won’t stop the cycle from returning. For many cats, heat repeats every 2–3 weeks in breeding season—so if you’re not planning to breed, spaying is usually the kindest long-term fix.

If you want to learn more about these eight key points, Explore our full care guide: How to Help a Cat in Heat: Comfort, Safety & Calming Tips

All these tips can ease the intensity of a heat cycle, and many cat parents find them genuinely helpful. But here’s the honest truth: they don’t stop the cycle from coming back. For most cats, heat returns every 2–3 weeks during breeding season—and that can feel relentless.

That’s why, if you’re not planning to breed your cat, spaying is truly the kindest long-term solution. It not only prevents pregnancy, but also brings relief from the hormonal rollercoaster she (and you) are on. We’ll talk more about when and why to spay shortly.

Conclusion

Having an in-heat cat at home can be a lot — the yowling, pacing, and constant attention-seeking can wear anyone down. But it helps to remember this isn’t “bad behavior.” Your cat isn’t being difficult on purpose — she’s responding to powerful, natural hormones.

The good news is that once you understand the timeline of a heat cycle, the clear signs of estrus, and the do’s and don’ts that actually help, the situation becomes far more manageable. You’ll know what’s normal, what needs extra caution (especially escape attempts), and how to keep both your home and your cat calmer through each phase.

If you’re not planning to breed, spaying is the most effective long-term solution. It prevents unwanted pregnancy and stops the cycle from repeating every few weeks during breeding season — which often means a calmer, more comfortable life for your cat (and more sleep for you).

At SnuggleSouls, we focus on real-life pet parenting solutions that make life better for animals and strengthen the bond you share. Thanks for reading — and if you’re in the middle of a heat episode right now, take a breath. You’re not alone, and with the right steps, you’ll get through it.

FAQ About How Long Are Cats In Heat

How long does a typical cat heat last?

On average, a cat’s estrus (heat) phase lasts 5–7 days, but can range from 2 to 14 days depending on the individual cat and whether she mates during this time.

How often do cats go into heat?

If unspayed and not pregnant, cats can enter heat every 2–3 weeks during breeding seasons (typically February through October). Indoor cats under artificial lighting may cycle year-round.

Do cats bleed when they’re in heat?

No. Unlike dogs, female cats usually do not bleed during heat. Any visible blood should be treated as abnormal and checked by a vet.

Can I spay my cat while she’s in heat?

Yes, although it’s slightly more complex due to increased blood flow to reproductive organs. Many vets still safely perform spay surgeries during heat—consult your vet for timing advice.

What age should I spay my cat?

Most vets recommend spaying at around 5–6 months of age, ideally before the first heat cycle, to reduce health risks and avoid unwanted behaviors.

Why does my male cat go wild when a female is in heat?

Male cats don’t have heat cycles, but they respond very strongly to females in estrus. They may spray, howl, try to escape, or show aggression.

Is my cat in pain during heat?

Not exactly—cats in heat are driven by hormones and may appear distressed, but it’s not usually physical pain. Comforting them helps reduce stress.

Can indoor-only cats still go into heat?

Yes. Heat cycles are hormone- and light-driven, not determined by exposure to other cats. Indoor cats will still cycle unless spayed.

References

ASPCA. (n.d.). Spay/Neuter Your Pet – Cat Care. American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Retrieved from https://www.aspca.org/pet-care/general-pet-care/spayneuter-your-pet

Llera, R. M., & Yuill, C. (2022). Estrous Cycles in Cats. VCA Animal Hospitals. Retrieved from https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/estrus-cycles-in-cats

Houpt, K. A. (2018). Domestic Animal Behavior for Veterinarians and Animal Scientists (6th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Root Kustritz, M. V. (2006). Reproductive behavior and physiology of the queen. Theriogenology, 66(5), 701–706. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0093691X06002378?via%3Dihub

Griffin, B. (2001). Proactive strategies to reduce feline overpopulation: Low-cost spay/neuter programs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 219(12), 1667–1671.